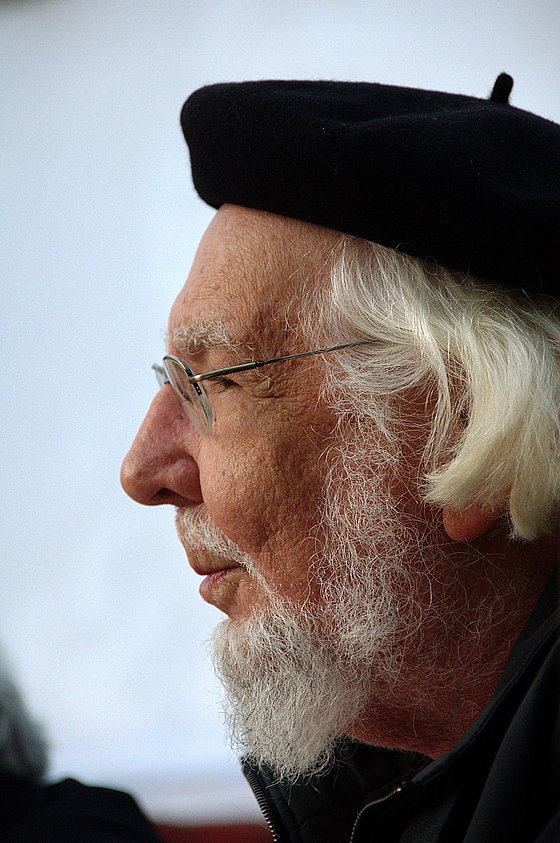

Ernesto Cardenal - the great poet of Latin America

Prof Dr Matei Chihaia / Romance Studies

Photo: Sebastian Jarych

Democracy cannot be taken for granted

Matei Chihaia on the 100th birthday of the great Latin American poet and Wuppertal honorary doctor Ernesto Cardenal

Ernesto Cardenal was a Catholic priest, socialist politician and poet. In what context did you first become aware of him?

Chihaia: After my habilitation, I had started a major research project on the poetry of ruins, which then increasingly centred on the idea of "zero hour" and "zero point" - these terms are no longer very familiar today, but they played an important role in my parents' generation: it was about the historical turning point that the end of the Second World War meant and the question of how literature and culture could deal with the literal and symbolic ruins left behind by the Nazi era. This model for thinking history can be applied to many situations, including current ones. In any case, this research was initially centred entirely on Europe until I met a Peruvian author at a conference, Félix Terrones, who now teaches at the University of Bern, and who told me that the concept is also very central to Latin American poetry. And she owes this to a long poem by Cardenal entitled "Hora cero", or "zero hour". It begins like this: "Tropical Central American nights, with lagoons and volcanoes under the moon and the lights of presidential palaces, barracks and sad curfews." This powerful image has become almost iconic for the problems of Central American countries, and it speaks about them from both a distance and a distance, as is typical of Cardenal.

He joined the opposition youth movement UNAP at a young age and fought - also in literature - against the dictatorial President Anastasio Somoza García. He almost paid for this with his life. What happened?

Chihaia: The poem is a small epic in which the origins and background of the Somoza dictatorship are described. Because the Somoza who ruled Nicaragua in Cardenal's time was the son of the first Somoza, who established the family rule over the country in the 1930s, Anastasio, whom we can call Anastasio the First. He was followed by his son Luis as president, and after his death, Anastasio, Anastasio the Second, took over the seat in the palace. It is a story that has happened in a similar way in many countries in Latin America and the world - just think of North Korea! - and should serve as a reminder that democracy cannot be taken for granted. Cardenal, who had studied literature and theology in Mexico City, New York and Colombia, returned to Managua in the early 1950s - a young man from the upper classes, educated at the best universities and, at the age of 29, already an intellectual who wanted to change the world, starting with his own country. So he joined an opposition movement and sympathised with an attempted coup in 1954, which was launched by some officers of the National Guard and failed miserably. Cardenal somehow escaped the bloody retribution of the regime, but had to go into exile: he became a novice in a Trappist monastery in Kentucky, where he continued his spiritual and poetic training. "Hora cero", a relatively early work, looks back at the failure and relates it to the historical struggle of Augusto César Sandino against the first Anastasio Somoza, and to the role of the United Fruit Company and other foreign companies in Nicaraguan politics. Overall, the poem offers a poetic overview of the country's history. In a way, it is an attempt to use poetry to remind us that it exists.

Ernesto Cardenal

CC BY-SA 4.0

He began studying theology in his mid-30s and was ordained a priest in Managua in 1965. During this time, he wrote the Psalms (Salmos, 1969), which are considered an expression of liberation theology. He was always involved in political issues throughout his life, wasn't he?

Chihaia: I think Cardenal's psalms are one of the great works of Latin American poetry. They arise from his own exile situation, which he projects historically back into the past - this time not into the 1930s, as in "Hora cero", but directly into the time of the people of Israel. On the one hand, his ordination as a priest was the aim of his own educational novel, an educational ideal that he had designed himself and in which dialogue with people, with nature and with God should be possible. On the other hand, during the Cold War, it was also a way of protecting oneself from persecution. There were corresponding organisations of international solidarity, such as Eastern Priests' Aid or Aid to the Church in Need, where I myself was involved as a young person, and from the 1960s onwards there was a growing awareness that the clergy in Latin America, who were fighting for social justice, were also being oppressed and threatened.

He wrote his best-known book in Germany, "The Gospel of the Peasants of Solentiname", in the commune of the same name. How did that come about?

Chihaia: Solentiname is the name of a group of islands in the huge Lake Nicaragua. Cardenal and a group of friends moved there after his ordination to the priesthood in order to realise the ideal of an original Christian community together with the local fishermen. Nicaragua is a country of great differences: on the one hand the cities on the Pacific with the educated upper class, on the other the rural areas and the Caribbean coast, which have traditionally been neglected by the state and where people live in very poor conditions. However, it is precisely this way of life that offers points of reference to the Gospel, which also speaks of the simple life: Peter is a fisherman, like the inhabitants of the Solentiname archipelago. "The Gospel of the Farmers of Solentiname" records the conversations that take place in this community about various texts from the Gospels and in which these people relate the message of Christ to their lives. Cardenal also encourages the community members to link the Gospels visually to their lives, resulting in these enchanting naïve paintings in which the story of salvation is transferred from the desert of Palestine to a tropical, colourful environment.

This commune ended dramatically in 1977. Why?

Chihaia: Cardenal had visited Cuba in the 1970s, where a group of scattered guerrillas under Fidel Castro from a rural area - the Sierra Maestra - had brought about a broad popular uprising "from below" and ultimately the overthrow of the local dictator. This myth of the Sierra Maestra, in which Che Guevara, among others, had also played a part, also inspired the neighbours in Central America. Could the Solentiname archipelago become the starting point for a Nicaraguan revolution modelled on the Cuban one? Cardenal was close to the Sandinista Liberation Front of Nicaragua, he advocated the idea of a Christian revolution and there were many in his community who wanted to bring about an overthrow by force of arms. When they occupied a National Guard barracks, the regime's tolerance came to an end: the Solentiname facilities were destroyed and Cardenal had to go back into exile.

The Nicaraguan Revolution took place in 1978/79, Cardenal returned to Nicaragua and took over as Minister of Culture for almost eight years. What did he achieve during this time?

Chihaia: It's difficult for me to answer this question because I know several people who worked closely with him and could provide much better information: first and foremost Lutz Kliche, who translated his poems and went with him to Nicaragua to assist him in the ministry. This cultural work was internationally visible: publishing houses and libraries were founded, festivals and exhibitions were organised. It went hand in hand with a literacy campaign, which was honoured by UNESCO and in the course of which around 400,000 Nicaraguans learnt to read and write. Unfortunately, the situation has deteriorated again since then, as the then Minister of Education Carlos Tünnermann laments: in 1980, 13% of people over the age of 15 were unable to read and write; by 2008, the figure had risen to over a quarter of this population group. The commitment to culture during his time as minister can already be seen in the stamps: in 1983, a beautiful series of Latin American poets was printed, including Pablo Neruda, who was admired by Cardenal, as well as many Nicaraguans such as the great Rubén Darío, whose portraits appear in front of their manuscripts. A double tribute to the culture of writing. Renamed the "Orden de la independencia cultural Rubén Darío", the State Prize was awarded in the same year to Julio Cortázar, the Argentinian storyteller who visited Cardenal in Solentiname and then wrote a highly acclaimed story about the destruction of the island community in 1977, "Apocalipsis de Solentiname". In any case, these authors believed that culture could have the last word.

The Catholic Church did not like Cardenal's political commitment and his closeness to the Liberation Church at all and Pope John Paul II even suspended him as a priest. But Cardenal didn't give up his stance, did he?

Chihaia: Yes, John Paul II and Cardenal had a lot in common: they were both poets and priests at the same time, both believed in the possibility of combining mystical religiosity and political commitment, both came from small states whose sovereignty was constantly in question, and both had enormous charisma. Tragically, they belonged to opposing parties in the Cold War. There were formal reasons for the suspension - a priest could not also be a minister - but in the background was the fact that the Catholic Church was anything but neutral. And John Paul II was closely associated with the political opposition in Poland, where clergymen were persecuted and murdered, so the idea of the Church being involved in the government of a socialist state must have been intolerable to him. In the Latin American context, however, Cardenal was celebrated for his commitment, also in contrast to the problematic role that a large part of the Catholic Church had played in the South American dictatorships and continued to play in the 1980s. There was also support for his stance from Germany: when the poet-priest was honoured with the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1980, the eminent theologian Johann Baptist Metz gave the laudatory speech.

Ernesto Cardenal and Matei Chihaia (right) during the honorary doctorate ceremony at the University of Wuppertal in 2017

Photo: Sebastian Jarych

In 2017, the University of Wuppertal awarded him an honorary doctorate. You yourself were present at the event. How did you experience Ernesto Cardenal?

Chihaia: I only spoke to him a little because I was focused on organising the event - I was mainly concerned with details such as the weakening batteries in the wireless microphone, the telephone announcement to dpa that he had actually received the honorary doctorate and arranging interviews with the poet. But it was touching to see how many people came who had known him all their lives and how much friendship and respect he exuded for everyone. It was also noticeable how he felt at home in Wuppertal, he had his favourite places and habits here. The award from the school of humanities and cultural studies came at a difficult moment in his life, when he had openly spoken out against the dictatorship of former liberator Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua and was subjected to all kinds of reprisals. At the time of his honorary doctorate, it seemed as if he would have to go into exile one more time, which gave the event a special significance.

His works in Germany were mainly published by Peter Hammer Verlag in Wuppertal. How did the contact come about?

Chihaia: That should really be explained by Hermann Schulz, the former publishing director who met Cardenal in Latin America when he was not yet so well known and ultimately made Wuppertal the centre of the European solidarity movement with Nicaragua. Peter Hammer Verlag played an important role in the worldwide boom of Latin American literature in the 1970s, together with Suhrkamp in Frankfurt, Seix Barral in Barcelona and Gallimard and Seuil in Paris.

He is considered one of Nicaragua's most important poets. What do literature lovers appreciate about his work?

Chihaia: I think lyrical poems can create relationships and connections, and in this way create meaning. They can be reassuring or unexpected, often opening up new perspectives on the familiar. This is the case, for example, with Cardenal's travel impressions from Germany, which can be found in "Heimweh nach dem Paradies", the volume published by Peter Hammer Verlag, which Lutz Kliche and Hermann Schulz have now edited: "In the house of a Westphalian farmer / fine curtains in front of the windows, / pictures, flower vases, modern lamps / "Why are the farmers in Nicaragua so poor?" / he asks me." Together with Karla Domínguez and Enrique Delgadillo, two young cultural workers born in Nicaragua and living in Germany, we are planning a week of activities in November 2025 that will make the survival of Cardenal's work visible. Domínguez, who is a musician, has set his poems to music for a concert in the Immanuel Church, and Delgadillo, himself an author and publisher, will offer a workshop on creative writing, following on from a series of seminars for master's students at the University of Wuppertal that has already begun.

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Matei Chihaia studied Comparative Literature, Romance Studies and Philosophy at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich and at the University of Oxford. He has been teaching French and Spanish literature at the University of Wuppertal since 2010.