Prof Holger Hoffmann / Architecture

Photo: UniService Transfer

Discovering da Vinci's world with the computer

Professor Holger Hoffmann from the Chair of "Representation Methodology and Design" on the infinite possibilities of digital design

"I can do it," says the native of East Westphalia when asked whether he can still draw on the drawing board and continues, "but I wouldn't do it anymore." At his chair, he mainly teaches techniques for the computer-aided conception, visualisation and materialisation of architecture. Drawing by hand still plays a role, of course, be it in the dialogue between architect and client or in the initial concept sketches. However, from the second semester onwards, descriptive geometry with perspective or shadow construction is taught on the computer. "It's better, faster, more efficient and, at the end of the day, more beautiful," Hoffmann states matter-of-factly. He is convinced that there is no longer an architecture firm today that only draws by hand. The reason for this is the ever-changing demands of digitalisation, which open up an inexhaustible design horizon.

The exciting thing about his chair is the integration of design and visualisation with the possibilities of computer-aided manufacturing technology. "I believe that about 25 years after the introduction of CAD (-CAD stands for Computer-Aided Design. A CAD system is like a kind of computer or workstation - which supports engineers in the development of products and systems - editor's note) in architecture represents a specialist area that is vital for students and graduates, because everything we teach here in terms of digital techniques, but also formal aesthetic issues, will later provide them with the necessary basis for their work."

Building Information Modelling (BIM)

Just how important this knowledge is in the international arena, where all communication is almost exclusively digital because people chat and communicate by email, is demonstrated by the process of Building Information Modelling, or BIM for short, which is currently being developed. This is an efficient, model-based process that connects experts worldwide so that they can plan, build and operate building and infrastructure projects together with greater precision. This creates virtual project spaces that can be accessed by participants from a wide range of trades. A digital space that allows specialist planners from all over the world to work together. Hoffmann sees the computer as a creative, digital medium that has also fundamentally changed design through its use.

Drawbot, the mechanical drawing robot

In order to better understand his work, the scientist reports on a current exciting seminar entitled "Drawbot" that he and his colleague, Heiner Verhaeg, offered last winter semester.

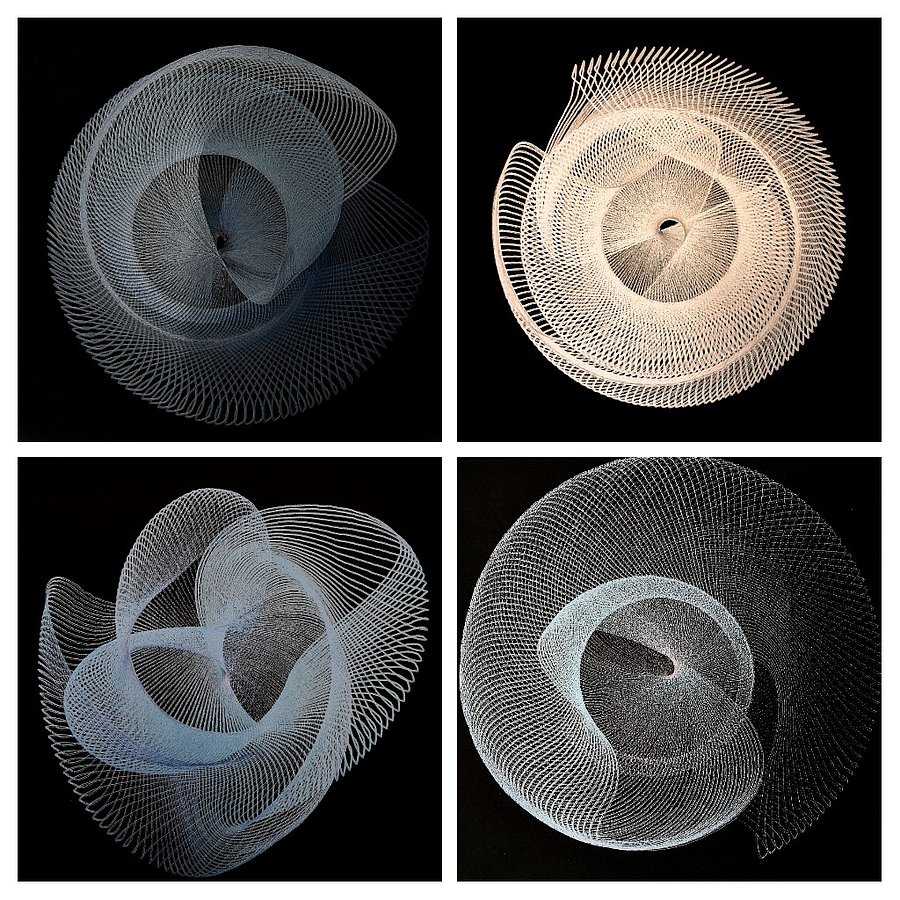

The College of Architecture at the Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering determines a special overarching theme for each Master's programme. Last year, the focus was on 'drawing'. Hoffmann explains: "As we have this digital background, we said we would investigate how a computer or a machine draws." In order to get started, however, the students first had to acquire specialised knowledge about programming digital geometries, digital production techniques such as 3D printing and - completely unusual for architects - gear teaching knowledge in order to be able to construct the machines that would later be used. Five drawing robots, Drawbots, were created, which produce different designs. Similar to the Spirograph toy from the 1970s, in which you could turn small, perforated plastic cogwheels with coloured pens in a limited frame, the Drawbots independently produce elliptical drawings in various sizes. In this way, the seminar groups built Leonardo-da-Vinci-esque, aesthetically pleasing machines that also produce attractive artefacts and learnt skills that are highly relevant for architects. The so-called "Circlebot", whose machine moves around the drawing, is particularly impressive. "For us, the didactic value behind it," explains Hoffmann, "is that what the students learn is scalable to other machines and design processes. Theoretically, we can use the knowledge that the students have gained here, particularly in programming, to design and control increasingly complex forms, including moving structures and constructions."

These mechanical models are architecture itself

Hoffmann talks enthusiastically about the course of the project, in which he was very impressed by the students. Despite methodologically difficult tasks, high intellectual demands and the cost-intensive purchase of components or a 3D printer, "we didn't lose a single group in this seminar," he explains, because unlike conventional working models, which are always representative in nature, "these mechanical models are architecture themselves."

Prof Holger Hoffmann / Architecture

Photo: UniService Transfer

Learning from role models

There are many imaginative, filigree examples of architecture. "If we look at the history of architecture, at a baroque or rococo church and recognise the ornamentation and geometric complexity, the creation of space and the vocabulary of forms go far beyond what we describe as architecture today," explains the 45-year-old. World-famous buildings such as the opera house in Sydney or the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao are examples that he likes to use to show students a canon of architectural possibilities. Works by the Iraqi star architect Zaha Hadid, who has had a significant influence on contemporary architecture, serve him as courageous role models in his teaching in order to arrive at new design possibilities by thinking differently.

one fine day

Hoffmann works in the same way in his Düsseldorf architectural practice "one fine day". Whether it's a mosque or a detached house in a rural setting, the architect always allows the viewer to recognise the context in which the building belongs. But on closer inspection, even the layman discovers that he has never actually seen anything like it. On closer inspection, the competition design for a mosque, which was also accepted by the imam, has vault structures that appear traditional but have never been seen before. Or the house built in a farming community in East Westphalia, which at first glance seems to fit in harmoniously with the rest of the housing landscape, but whose roof construction and layout the observer cannot explain, even when walking round the building. "This is also something that the client enjoys. He says that visitors who come to his house don't understand it at first. For example, they can't tell whether the house is large or small."

For Hoffmann, the chair in Wuppertal and his office in Düsseldorf form a kind of symbiosis. "Our aim is to build a bridge between the topics that we develop here in Wuppertal and the topics that we develop in the office. Combining both locations gives us the freedom to think about projects differently."

Building icons in Wuppertal

Not every excursion can take in the world's great building examples, and it doesn't have to. Hoffmann himself is familiar with various examples of architecture here in Wuppertal and the surrounding area that are also pioneering in international comparison. "It starts with the Neutra House (Villa Pescher) on Freudenberg, which has remained largely unchanged. Three years ago, I had the great privilege of visiting the house with my students. The current resident gave us a guided tour. Haus Pescher is a world-class icon from the 1960s. The house is so sophisticated in its spatial construction, materialisation, the relationship between the house and garden, etc., that you don't often see that." But the Villa Waldfrieden in the sculpture park or the pilgrimage cathedral in Neviges are also buildings that have long been sought after worldwide.

Leonardo set an example over 500 years ago. Think differently, don't be fazed and develop things that go beyond the ordinary. Hoffmann continues this philosophy digitally and says: "For me, architecture is not a discipline in which only existing knowledge is passed on, but in which we speculate about the future of our disciplines. It is of central importance to us that our students learn to question what we - supposedly - always do and to find solutions that are more interesting than what we usually do. That is architectural progress."

Uwe Blass (interview from 19 March 2019)

Prof Holger Hoffmann is Professor of Representation Methodology and Design at the University of Wuppertal and founder of the Düsseldorf-based architecture firm one fine day. After graduating from the Münster School of Architecture, he worked as an architect at Bolles+Wilson in Münster and, after graduating from the Städelschule in Frankfurt, at UNStudio, Amsterdam. Since then, his interests in practice, teaching and research (among others) have focussed on the computer-aided design, representation and production of architecture, with a particular interest in typological and tectonic issues