"The Magic Mountain" was published 100 years ago

PD Dr Arne Karsten / History

Photo: Sebastian Jarych

The longest cure in history

Thomas Mann's novel "The Magic Mountain" was published 100 years ago

An interview with historian Arne Karsten

Where did the idea for 'The Magic Mountain', which was published on 28 November 1924, come from?

Karsten : As is so often the case with Thomas Mann, the idea came from his own direct experience of life. His wife, Katia Mann, fell ill in 1912 and it was suspected that she was suffering from closed tuberculosis, but this was not subsequently proven to be the case. She then had to go to the high Alps for a cure - according to the state of medical knowledge at the time - and travelled to Davos. Thomas Mann visited her there and gained his first impressions of the self-contained world of a lung sanatorium. Katia Mann also stayed in Arosa afterwards and wrote many letters, some of which he used as material. Unfortunately, these were lost when the family gave up the house in Munich in 1933 during the Nazi era. The archives were probably destroyed in an air raid.

What is the novel about?

Karsten: The novel is about a young Hamburg patrician's son who travels to the Berghof sanatorium in Davos for three weeks in the summer of 1907 to visit his cousin who is suffering from tuberculosis. In the end, these three weeks turn into seven years in which the young Hans Castorp, as the protagonist is called, undergoes a multitude of experiences, falls ill himself, falls in love with a sick Russian woman who is also a guest at the Magic Mountain and goes through what could be called a Bildungsroman, following Goethe's example. The simple, albeit appealing young man becomes something of a philosophical mind under the influence of the witty, albeit seriously ill atmosphere on the Magic Mountain.

The hero of the novel, Hans Castorp, is a very unusual character. What makes him so special?

Karsten : Paradoxically, Hans Castorp's speciality lies in his mediocrity. He is a very average, likeable contemporary, but by no means endowed with special gifts. This is precisely why he becomes such an ideal test character for the magical world of the Alpkur. After all, he is receptive to the impressions he encounters there. And so Thomas Mann writes, 'we may describe him as something more than average'. In the end, it's not a story that happens to everyone, that's how Thomas Mann characterises the young Hans Castorp, and this ability to be educated and receptive to the intense impressions of the magical mountain world is what makes the protagonist so special.

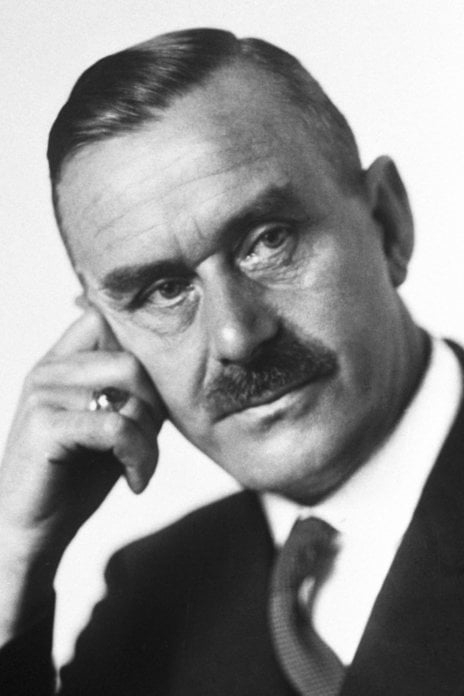

Thomas Mann 1929, public domain

Thomas Mann worked on this novel with long interruptions. Why?

Karsten : Above all, the First World War intervened. Thomas Mann writes about this in great detail in the interspersed 'Reflections of an Unpolitical Man' under the impression of the political and then military conflict, which revalued all values and destroyed the everyday world. It signalled the end of the bourgeois age, and under this impression he could not continue writing. He had tried, but it didn't work, he first had to come to terms with his own political position in the world, and this reckoning cost him four years of his life and a lot of nerve.

Then came a few smaller works in order to gain some distance from the extremely exhausting and alienating preoccupation with politics. He then returned to The Magic Mountain, which was initially intended as a short novella, a counterpart to the story "Death in Venice", but only developed a will of its own over time, under the author's hands, and then took on the monumental proportions of almost 1000 pages.

The novel attracted an enormous amount of attention from readers and had a print run of 100,000 copies after just four years. What fascinated readers so much at the time?

Karsten : Thomas Mann obviously hit the zeitgeist with this parable. He describes Hans Castorp's thoughts on the attitude to life when time itself responds to the consciously or unconsciously but somehow posed question of the higher purpose and deeper meaning of an action with a hollow silence, when it nevertheless reveals itself inwardly as hopeless, hopeless and pointless despite all the outward bustle: Then, especially in cases of more honest humanity, a certain paralysing effect is inevitable. This is the experience of the young Hans Castorp, which makes him receptive to the Zauberberg atmosphere, a very easy life dedicated solely to illness and the fight against illness, without obligation, without work, without any tasks, with plenty of free time to think about the meaning of it all. And this question of meaning, this question of where to, where from, what for, was asked intensively before the First World War with all its destructive effects and even more so afterwards. The Magic Mountain therefore hit the nail on the head for a society in search of itself.

But Thomas Mann also annoyed readers. His colleague Gerhart Hauptmann did not speak well of him for a long time. What had happened?

Karsten : Thomas Mann had portrayed Hauptmann in the character of Mynheer Peeperkorn, a late but important character in The Magic Mountain, and also caricatured him a little, as he often did. He repeatedly said: "I have invented nothing in my work." He repeatedly transformed people, impressions from the present, from his own world of experience, and remodelled them into characters in the novel. This use of living figures to ironise and slightly caricature them and turn them into characters in his novels was repeatedly resented. Gerhart Hauptmann was relatively generous, although he was disgruntled for a moment, but very soon the two were reconciled.

Thomas Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929. Experts categorise the novel as an anti-educational novel. What does that mean?

Karsten : Perhaps the novel should rather be seen as a parody of the Bildungsroman, insofar as the classic Bildungsroman, modelled on Goethe's 'Wilhelm Meister', allows the protagonist to become more and more mature, more and more fit for life. Hans Castorp becomes wittier, but not more fit for life. In the end, he marches off to fight in the First World War. It is left open how it ends, but the author strongly suggests that Hans Castorp does not survive this war. So education is not redemptive here and does not lead to the character finding his place in the world.

Death always has a special significance throughout Thomas Mann's work. Why was it so important to him?

Karsten: On the one hand, because of earlier personal experiences. His father died in 1891, when Thomas Mann was 16 years old. Shortly before that, he had intensely experienced the death of his beloved grandmother. He grew up with the experience of death from an early age. On the other hand, it is his personal antidote to a time characterised by hollow optimism about progress, in which the very thing that makes Hans Castorp, who is also fascinated by death, so influential. In a time that knows neither out nor in with hectic activism, but which represses the questions of meaning precisely with this activism, it is an important antidote: to remember that all human activity is finite and all human beings are mortal. Without the awareness of death, there is no philosophy. Nevertheless, one of Hans Castorp's central insights is the key sentence: for the sake of love and kindness, man should not allow death to rule his thoughts.

In his 50th birthday speech, Thomas Mann said: "If I have one wish for the posthumous fame of my work, it is that it should be said to be life-friendly, even though it knows about death." Can you explain that?

Karsten : Exactly what is expressed in this sentence: a life that represses death remains superficial and banal. It exhausts itself in practical, everyday activities, but systematically avoids the essential questions of where from, where to and why, i.e. what distinguishes humans from animals. This busyness is broken up when we consider the end. On the other hand, the sole backward-looking attitude, the fixation on the finite nature of existence, is detrimental to life because it prevents us from coming to terms with life. This is what the Magic Mountain guests suffer from, what makes them ill: that they don't want to take it upon themselves to face the challenges and labours of existence.

Uwe Blass

PD Dr Arne Karsten (*1969) studied art history, history and philosophy in Göttingen, Rome and Berlin. From 2001 to 2009, he was a research assistant at the Institute for Art and Visual History at Humboldt University Berlin. He has been teaching as a junior professor since the 2009 winter semester and as a private lecturer in modern history at the University of Wuppertal since his habilitation in 2016.