Images in Christian Art

Dr. Angelika Michael / Protestant theology

Photo: Private

Is the Divine Representable?

Dr. Angelika Michael on the development of pictorial works in Christian art

"In the first 200 years of church history, there is no Christian art," says Angelika Michael, a lecturer in Christian art and the didactics of religion in the Protestant Theology Department at Bergische Universität, and this is initially simply due to the fact that the Christian religion was not recognized in the Roman Empire of the time, and Christians had no way of representing their faith and worship in public. In addition, "they also wanted to set themselves apart from paganism, which was characterized by the multitude of images of gods, by linking worship to an image of God," says the theologian. "It was said that the divine was absolutely unrepresentable, but that every human being was called to become more and more the image of God, - and there was no need for an image work." Already at this point the topic of the representability of the divine, which was sharply discussed many years later in the so-called image controversy, has its origin.

What is Christian art?

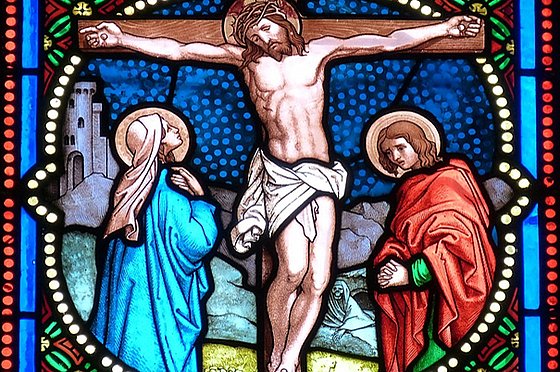

"Christian art is the name given to all representations that put biblical or even church-historical events or persons before the eyes," the scientist explains. In a broader sense, it includes everything that was created in the context of private piety and public Christian worship, especially architecture, i.e. the entire history of church building. The development of Christian art, he said, has been a long process, beginning with the first symbols. "And then came the Constantinian Turn" (In the Constantinian Turn, Christianity gained influence in the Roman Empire and was finally elevated to the status of state religion in 393 AD, editor's note), Michael formulates what is probably the most concise caesura in early church history. After that, there was representative building, representative worship, and Christianization in all areas of society. "Basically, then, in the Middle Ages, all art is Christian art." The church often acted as patron, and rulers also designed their castles or palaces with the consciousness of being Christian rulers.

The works of art, Michael explains, were initially the normal subject of art history. "Descriptions of art already exist in the literature of antiquity and late antiquity, in the Renaissance we find artists' vitae as well as reflections on the question of what art is in the first place," she says, but it is only since the second half of the 18th century that art history has existed as a science. At the theological faculties, for a time the study of Christian art was part of the study of church history, and here there were chairs of "Christian Archaeology" - these are now mostly assigned to the philosophical faculties.

Is it possible to represent a divine person?

But how can the contents of faith be represented? The problem here is that a relationship with God is by its very nature not visible, says Michael, and the approach was to first find symbols, then in the further course to try to depict the biblically reported actions of Jesus. "And that gave rise to the task of depicting this man, who the Christian faith says is both human like us - and God." This, in turn, gave rise to traditions of representation that theologians eventually reflected upon and over which a dispute arose. "So there were theologians who said it was impossible to represent Christ, because he is God, and the divine is not representable. So this person as a divine person is also not representable." On the other hand, proponents argued the necessity of representing Christ. This argument was carried on for centuries in the so-called Byzantine Image Controversy (The Byzantine Image Controversy was a period of theological debate in the Orthodox Church and the Byzantine Imperial House during the 8th and 9th centuries. It was about the veneration of icons ed.). The dispute was mainly about the images of Christ, although other images were also important: for example, pilgrimage arose and believers collected earth or water from holy places, or took images of saints to which they attributed miraculous powers. The decision in this dispute, which is still valid today, was formulated in 787 A.D. at the seventh ecumenical council in Nicaea, convened by Emperor Constantine VI or the regent, his mother Eirene. According to Michael: "The decision at that time was: the images may and should be venerated. They have a good meaning in the life of Christians. So what was there before anyway was now officially recognized. Especially in Orthodoxy, this decision really comes to bear until today. There the icons are part of it, images that visualize the divine person or the saints." An important sentence of the Council's decision says that the honor paid to the image is passed on to the original image, so that in truth it is not the material object that is honored, but the divine person in the image. "The image, for Orthodoxy, to this day, is the mediator of the divine and plays a great role in the decoration of church interiors - the picture wall is one of them -; for Orthodox piety, the image reveals the divine" says Michael, "even to every household there is an icon."

Here, then, is a great contrast with the other monotheistic religions. "In Judaism and also in Islam, it is forbidden to attempt any representation of God. It is unusual not only in Islam but also in Judaism to furnish the worship space with any figurative representations. Islam generally prohibits any depiction of a figurative nature in the direction of prayer, and all depictions of the Prophet Muhammad are considered offensive. When you deal with the issues of the image dispute, you clarify your own tradition, but you also come to understand other traditions better."

Banning of imagery in the Reformation era

A second wave of controversy began in the late Middle Ages and reached its peak during the Reformation, when pictorial works were removed from churches and in some cases destroyed. Again, representations of Christ, as well as paintings and sculptures of the saints, were called into question. "The point of all the reformers was that when man seeks divine help, he should turn to God alone," Michael explains. "The saints were not to be venerated in the way that supplications were addressed to them. Where certain supplications were considered particularly effective before certain images, and where images were venerated, all reformers agreed, those images had to be removed." When it came to the image of Christ, however, the reformers' opinions differed, the scholar knows. Zwingli and Calvin, for example, virtually joined the arguments of the Byzantine opponents of images; and they said that "whenever man has something that is a representation of the divine, he tends to the superstitious view that with this representation he possesses and disposes of the divine itself." This strictly Reformed tradition can be seen even today, he said. "When one encounters worship spaces in strictly Reformed tradition, there is no imagery there, nor any sign of the divine. No candles, not even the sign of the cross," says Michael. Luther, on the other hand, took a more moderate view and said that if you enlighten and preach correctly, then you can certainly allow sculptures. They were not needed, nor should they be venerated, but they could be reminders of the content of the faith.

The representations of Jesus Christ are followed by representations of God the Father.

In fact, everyone would always have held to the basic insight that the divine cannot be represented. Nevertheless, says Michael, "in the late Middle Ages a tradition of representation established itself in which not only the incarnate God, but also the first divine person, the invisible omnipotent eternal Father is depicted, and this in the form of an old man. There played on the one hand a prophet vision a role, with which one justifies such pictures, besides it seems to be somehow obvious because of the father name, if one represents the son as a man of middle age, then to represent its father as an older man." But one has to ask oneself whether such images are helpful or rather stand in the way of an understanding, Michael formulates and continues: "When I put images in front of people's eyes, that is also a basic insight of these whole image disputes, they have a very immediate effect. And if I fix the idea or the affect by a picture work, then the word, in which for us in truth God reveals himself, hardly comes against the picture any more. It is essential to take this into account in terms of religious education."

The Gero Cross in Cologne Cathedral

A unique monumental work of art can still be found today in Cologne Cathedral. The so-called Gero Cross dates back to the 10th century and made a tremendous impression on the people of its time. "It used to stand in the old cathedral in the middle of the church, but today it can be seen on a wall with a sun set in baroque style and thus somewhat transported into a heavenly sphere." In its placement at the altar of the cross in earlier times, the impression was apparently so realistic, Michael explains, that contemporaries actually had the experience of an encounter with God in view of its size. However, since people did not want to attribute this power to a work of art without further ado, the legend soon arose that the cross had been completed by God himself and that it actually contained what it represented. A chronicler wrote around the year 1000 A.D. that there had been a gap in the head of the sculpture, into which Archbishop Gero had placed a relic of the cross as well as a consecrated host, whereupon the gap closed. "One justified the experience by the legend," explains the theologian. "They thoroughly examined this work of art during a restoration and found nothing of a cross relic or host. You realize how new and unfamiliar this presence experience was."

A church interior speaks its own language

Works of art of all kinds can be found in almost every house of worship today. Well-known artists have left their mark over the centuries in the form of paintings, sculptures or windows. In the 20th century, names such as Chagall, Lüpertz and Richter drew thousands to the churches to gaze at the splendor of the monumental windows. In the wake of many church departures, one may wonder if churches will become an alternative to museums in the future? However, the art history graduate sees it differently. "I would see a difference to visiting a museum, because in the museum I usually have a certain distance. You have catalogs there, inform yourself and pace things. In the church, on the other hand, the space works as a whole. You might go there first to see this one work of art, but you enter the space, and it often speaks its own language. Perhaps one can have the experience that one is lifted up as an individual in a large context of meaning. An appropriately designed church space has a message without words."

Church rooms in Wuppertal

You can also experience this message without words in your own city. Michael lived above Bergische University for a while and visited the surrounding churches. In the Laurentiuskirche, for example, she likes the clearly structured, very bright and precious but sparsely furnished space. "And I particularly like the Christuskirche here on the Grifflenberg. It was very badly damaged during the war, and then in the 1950s it was given a completely modern interior design, which is very successful. You have these slender supports, you have the clear, bright space. The apse window is particularly beautiful. It's a depiction of Christ coming again, very varied in detail, and just when the sun is shining, the image is one glowing light. It's very impressive."

"Religion," she says at the end, "is not only worldview or ethics, but religion has to do with the relationship to the infinite," and there, perhaps, art can express something that cannot easily be put into words.

Uwe Blass (conversation from 08.09.2021)

Dr. Angelika Michael is a lecturer for Christian art and didactics of religion in the Protestant Theology of the Bergische Universität.