Prof. Dr. Tatjana Tönsmeyer / History

Photo: Private

Picasso's artistic response to the Second World War

The historical program accompanying the current Picasso exhibition in Düsseldorf was developed under the direction of Wuppertal history professor Tatjana Tönsmeyer

In 2020, two internationally acclaimed exhibitions on Pablo Picasso will open their doors in Berlin and Düsseldorf."Pablo Picasso. War Years 1939 to 1945" is the Düsseldorf title of an extraordinary presentation at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen K20. In cooperation with the Chair of Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Wuppertal, under the direction of Prof. Dr. Tatjana Tönsmeyer, a rare and unusual approach to the work of the Spanish genius has been created. The curator of the Kunstsammlung NRW, Kathrin Beßen, and the staff member of the Education Department of the Kunstsammlung NRW, Angela Wenzel, specifically approached the Wuppertal scholar because they were "looking for clues to understanding Picasso beyond classical art history," Tönsmeyer explains. "Picasso is considered a genius. He created great works of art. But the fact that he definitely also reacted to his everyday life, that he reflected it, that he was precisely not only looking for the best artistic solution, but was also involved in the course of time, is something that the public is perhaps not so aware of. That's the situation the two curators wanted to respond to." That the exhibition organizers turned to the Wuppertal Chair of Modern and Contemporary History was no coincidence. Tönsmeyer has been researching occupation experiences in the years of World War II in a European perspective for years. "We are currently preparing a large source edition. That's 600 sources that will be published in English, documenting experiences of deprivation and hunger throughout occupied Europe" explains the researcher, because "it's not really clear to many people, especially in the Federal Republic, what occupation meant for our neighbors."

Hunger: this is the world in which Picasso lived

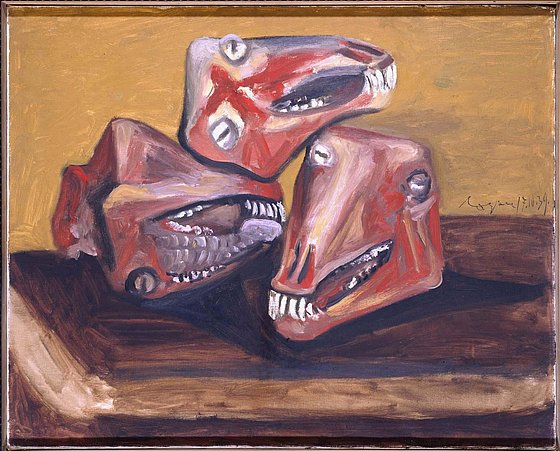

Hunger characterized everyday life almost everywhere in occupied Europe during the war years, not only in France, where starvation deaths were rare, but also to a large extent in the Soviet Union. In cities like Kiev or Kharkiv, more people died of hunger than of combat, the researcher says. But Greece also counted many starvation deaths; people died in some cases in the middle of the street. Even in the Netherlands, almost 22,000 people lost their lives to malnutrition in the winter of 44/45. The German soldiers stationed with our western neighbor, however, reported at home about their "life like God in France. In doing so, they completely ignored the starvation situation, caused not least by German exploitation. "As early as the fall/winter of 1940/41", the researcher knows, "the prefect of Paris warned against eating cooked cat meat - because it could transmit diseases." And that's where Picasso comes in again. Since 1936 he worked in Paris in a studio at 7 Rue des Grands-Augustins, where Guernica was created and which he also used as an apartment since the spring of 1939. He remained there, apart from his stay in Royan near Bourdeaux in 1939/40, until the liberation of Paris in August 1944. His works created during this time thus also reflect the world in which he lived.

'La fenêtre', an artistic response to the war

Slowly, the chair team is approaching the task of preparing a historical program to accompany the exhibition. To this end, they are first sifting through photos of the works presented in the exhibition by an artist whom Tönsmeyer quotes as saying "he did not paint the war directly, but the war certainly had an influence on his paintings, and to work out the connections is something he will leave to future generations of historians." The Wuppertal historian explains this new task plausibly by Picasso's painting 'La fenêtre'. "'La fenêtre,' the window, from 1943, shows an attic, with an open window through which you look outside. You can see other roofs and it clearly gives the impression that it is a summer picture. Nevertheless, a radiator together with its supply lines takes up almost a quarter of the picture. As a historian, I then ask myself: why did Picasso paint a radiator?" And thus begins the reflection and the incorporation of scientific findings from her research work: "The shortage I was talking about did not only concern food. It also concerned medicines, housing, it concerned water, electricity and heating," she explains and continues, "we also know that the winter of 1940/41 was particularly severe, that for almost two months the thermometer showed temperatures well below freezing. The writer Irène Némirovsky writes that old people and children wouldn't leave their beds for weeks because it was the only place where people didn't freeze." When viewed in this light, the image takes on another dimension. In terms of contemporary history, the seemingly banal motif of the heater provides an artistic response to the war. Says Tönsmeyer, "If Picasso said the war certainly had an influence on his paintings, I would recognize something like that here."

Wuppertal students take over guided tours

The accompanying historical program, for which the scientist is responsible, supplements the classical art-historical tours with four historical tours, which are taken over by students and doctoral candidates of the chair. "These are all young people who are affiliated with my chair and who explicitly address this historical dimension. They do tours where they talk about what the time contexts are and what you can still see in the paintings." In addition, the art collection organized what it called a focus talk in advance of the exhibition, to which the students were also invited. "The two curators asked a small group of people - both those who have something to do with art and those for whom that is less the case - to have a conversation and work out with them what kind of approaches there actually are to Picasso. This is yet another approach to the subject, one that is less familiar to us from our everyday academic lives. Seeing how major exhibition houses do this is therefore an inspiring experience and enrichment." In addition, Tönsmeyer has written several catalog articles and organized a reading with a professional actress who will recite source texts of various kinds. "Because the supply shortages in relation to France and Paris, but also in general to occupied Europe, are after all little known to a German public," she says, "we have selected a set of sources and won over the Berlin actress Anette Daugardt. She reads about 15 sources. And that's exciting because she's able to give each source a different voice in an outstanding way. There are diary entries, but also cooking recipes (what do you cook when there is nothing left?) and sometimes completely abstruse, German occupation documents in the form of market regulations. Endless lists describe everything that is not allowed to be sold and the serious penalties that apply. And then, as the last sentence, it says: "Everything else is freely for sale." In these documents, Tönsmeyer's lecture brings both the occupiers and the occupied to life. The museum audience thus hears scientifically compiled material in an artistic presentation.

In preparation a novel from the time

Tönsmeyer sees the appeal of this cooperation above all in its interdisciplinarity. "Art historians and historians begin to talk to each other about the images and report what they see in them and what they can recognize from their respective contexts. Questions change when you can participate in knowledge and approaches of the neighboring discipline." The scholar's work is done, and the exhibition Pablo Picasso. War Years 1939 to 1945 runs in Düsseldorf starting Feb. 15. "On a very personal note," she concludes, "I find it very exciting how much history there is in the paintings, how much context of time. I think if you have the time and the inclination, I would advise reading a novel from the period. I would suggest Irène Némirovsky, a Jewish woman from Ukraine who came to France with her parents as a child and became a writer as a young woman. She did not survive the war, but was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942. She leaves behind 'Suite francaise', a novel about the great escape in the summer of 1940, and in it she also describes life in the provinces." (The film of the same name, starring Michelle Williams, was made in 2015. Ed. note) "Picasso may show the capital, but Némirovsky shows the occupation. This coexistence of occupiers and occupied, which you don't see in Picasso's paintings. I think it gives you a sense of the time again."

Uwe Blass (Interview on January 31, 2020)

Tatjana Tönsmeyer studied history, Eastern European history, political science and journalism/media studies at the universities of Bochum and Marburg and received her doctorate in 2003 from the Humboldt University in Berlin, where she worked as a research assistant until 2011. She habilitated at the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena and has held the Chair of Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Wuppertal since 2011.