First factory on the European mainland built by a man from Elberfeld

Prof. Dr.Ing. Christoph Grafe / History and theory of architecture

Photo: UniService Transfer

A man from Elberfeld built the first factory on the European continent

Christoph Grafe on the factory owner Johann Gottfried Brügelmann and the importance of everyday architecture

"The appreciation of industrial buildings in Germany only began after the Second World War," says Christoph Grafe, professor of architectural history and theory at the University of Wuppertal. Yet all these buildings in the course of early industrialisation had already stood for the strong entrepreneurship in the Bergisches Land since the middle of the 18th century in what was then the Grand Duchy of Berg. One of the leading figures at that time was the son of the mayor of Elberfeld, Johann Gottfried Brügelmann (1750 - 1802), who built the first factory on the European mainland in Ratingen.

Cromford factory in England, CC BY 2.5

Wuppertal textile companies had their eye on developments in England

Almost 100 years before the start of industrialisation in Germany, the process had already begun in England. There the world's first factory was built in 1771, the so-called Cromford Mill in Derbyshire. "This fact is very interesting, because the English word for factory is mill and the first factories often needed water power," explains Grafe. "Several processes are running simultaneously here. We have a concentration of certain developments that could be described as industrialisation, starting with the move from small-scale manual work to concentrated processes with machines, using water power and then, over time, also using steam engines." The mainland lagged a little behind this development, where the first industrialisation took place in Belgium and France. Germany - with one exception - did not play a significant role, explains the expert: "The textile companies in Wuppertal, however, had their eye on developments in England very early on. This was also one of the reasons for Friedrich Engels to go to England later. Brügelmann obviously knew very well what was happening in England and tried to bring some of this success to the Bergisch region." The fact that the Bergisch region was still a territorial, political entity with laws that particularly favoured commercial activity was an advantage. "At that time, the Bergisch Land was still part of the Duchy of Berg which really was a pioneering region in Western Europe for all kinds of commercial settlements because there was a supporting policy. It was a territory where success was actually more of economic rather than military importance, and in which a bourgeois, very dense commercial landscape had developed. The so-called Wuppertal Garnnahrung is a very early example of this."

Ratingen spinning mill, today industrial museum , CC BY-SA 3.0

Competition in the valley leads to the founding of the company in Ratingen

Although Brügelmann wanted to base his findings in the valley, he encountered resistance from the competition in Elberfeld and ultimately changed his plans and built a yarn factory in Ratingen. Grafe explains: "There were people who were politically influential in the area, and he was possibly too innovative for them. There was also the aspect of more available space, away from the narrow valley. In addition, Ratingen was an impoverished town at the time; there had been early industry there in the Middle Ages, but this had all been lost in the Thirty Years' War, although the town even had links to the Hanseatic League. With the support of the Duchy of Berg, Ratingen was an interesting place for Brügelmann to settle. He pursued an industrial policy that was supported 'from above', so to speak."

Industrial espionage in the English kingdom?

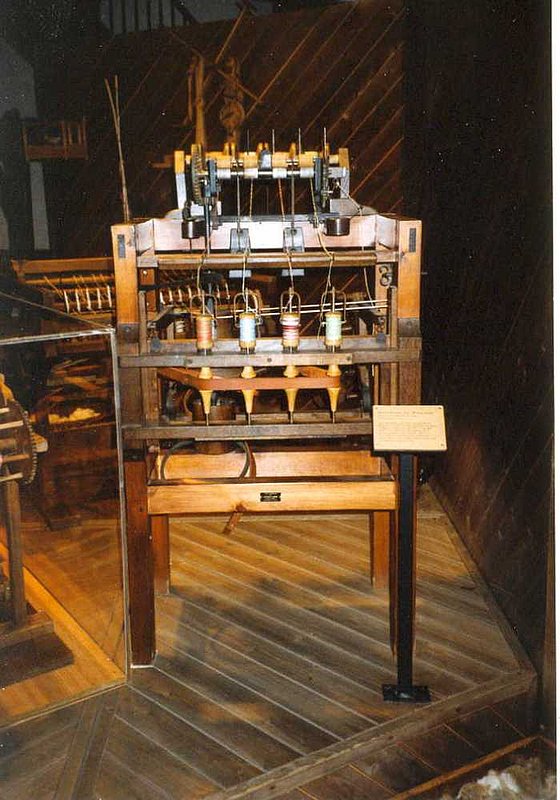

There is talk in the literature that Johann Gottfried Brügelmann engaged in industrial espionage in England. "The exact circumstances are still not one hundred per cent clear," Grafe replies. "There are probably indications that he had contacts in England via a friend, but whether it was the case that he brought an English factory worker here who entrusted him with company secrets is impossible to find out." What is certain is that Brügelmann obtained information about the use of the so-called 'waterframe', a spinning machine with independent drive from a water wheel, which the founder of the spinning mill in Cromford, Richard Arkwright, kept under strict lock and key. Curiously, he also named the textile factory founded by Brügelmann in Ratingen Cromford.

Waterframe in the historic centre of Wuppertal, CC BY-SA 3.0

Factories were often very isolated

The Cromford factory in Ratingen was designed as a five-storey building so that work could be carried out on several levels. "You mustn't forget that home-based work in the Bergisch region often took place in multi-storey houses," Grafe explains. "If you look at the old spinning and weaving mill buildings from the pre-industrial era, you can often see that the yarn was processed in the attic. The multi-storey building was already part of the textile factory." What is interesting from an architectural and urban planning point of view is the fact that these factories were generally not built in towns, but in very, very isolated locations in remote villages, and that certainly had something to do with the importance of water power. "It is typical of the Bergisch region that even in the late Middle Ages, industries were not located in the towns but in the countryside, because they often settled on small rivers and streams where it was possible to utilise water power." Cromford in Ratingen was not exceptional from an international perspective, but for mainland Europe and the Rhineland in particular, the factory is special and has a unique selling point.

Industrial buildings are considered pioneers of modern architecture

"The buildings are very much characterised by utilitarian thinking," Grafe says, "we have an architecture here in which all the rules about position and function, i.e. what had to characterise a building, did not apply." In addition, these industrial buildings were not recognised as architecture in the 18th century. "It took a very long time until these buildings were recognised as being worthy of monument protection and for them to become common property." And here, again, England has been a pioneer since the 1950s. "The term 'industrial archaeology' was coined there, but German heritage conservationists don't appreciate it," the expert explains smiling. In Germany, it even took until the 1980s for this type of architecture to be recognised. Although people had been aware of the utilitarian idea and purist aesthetics of simple construction since the beginning of the 20th century, the appreciation of these industrial buildings, which were part of the development of modern architecture, only came after the Second World War. "The concept of monument preservation was suddenly expanded to include industrial buildings or buildings from the industrial revolution and the Gründerzeit buildings. This development in appreciation sensitised architects to the architectural qualities of this type of everyday architecture." One problem arose in that many of these large factory buildings, which were very remote, had been empty for a long time towards the end of the 20th century and it seemed difficult to find another use for them. The situation is different in Wuppertal and Ratingen, as the buildings are located in an urban centre. The former Brügelmann spinning mill is now home to the LVR-Industriemuseum.

Brügelmann manor house in Ratingen, CC 0

Factory ensemble from the early phase of industrialisation

The Cromford spinning mill in Ratingen with its factory buildings, the working class housings, the manor house, the park in front of it and the river behind it, is one of the river Anger behind it, is one of the few factory ensembles from the early phase of industrialisation whose buildings have been preserved for posterity. Brügelmann's mansion with its park was regarded as the factory's control centre. With 14 rooms on three floors and an area of 320 square metres, the circular garden hall still fascinates visitors today. The house is based on plans by the electoral master builder Nicolas de Pigage. He had already built the electoral palace in Benrath, a baroque building, a few years earlier. "The Brügelmann mansion is often compared to Benrath," Grafe says, "but in principle, this is a thoroughly bourgeois residential building. It may be larger than the townhouse of an industrial family in Elberfeld, but it is a building in which a certain sober utility determines the floor plan. It is not a courtly culture, but a deeply bourgeois one. And that is not disappointing, because this is an entrepreneur realising his own living culture, only on a larger scale." The neighbouring garden harbours a contradiction for the Wuppertal architect. "The moment he designed the garden as a baroque garden, it was actually a bit old-fashioned, because the English landscape garden of the mid-18th century had already been introduced everywhere in Germany. In a way, the garden stands in opposition to what it embodies itself. In the 18th century, the baroque garden tended to be associated with France, with Versailles, in other words, with aristocratic principle and form. The English garden is more associated with the idea of free trade and entrepreneurship. Brügelmann was actually an exponent of English entrepreneurial culture and not the aristocratic culture of the custom garden. That's an interesting contradiction."

Medallion: Johann Gottfried Brügelmann, public domain

Brügelmann, an important entrepreneur from Elberfeld

In a letter, Johann Gottfried Brügelmann writes "...not used to being deterred by difficulties, I hope to clear all obstacles out of the way!" The successful entrepreneur always took this credo to heart. His work was very profitable and he was considered one of the richest men in the Rhineland at the time. He was an entrepreneur through and through, expanding in Cologne and Rheydt and buying castles in the vicinity of Ratingen, as these were tax-free at the time. He set up charitable foundations and was a member of the “Erste Elberfelder lesegesellschaft” (First Elberfeld Reading Society). "He was a representative of a culture of entrepreneurship that did not exist so strongly in Germany at that time," says Grafe. "Here in the Bergisch region, he fitted into the entrepreneurial culture based on strong families that existed in the Grand Duchy of Berg due to the active trade and later industrial policy. He was one of the most adventurous entrepreneurs in this area."

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Christoph Grafe has held the Chair of Architectural History and Theory at the University of Wuppertal since 2013.