Cardinal Richelieu - a clever power politician

PD Dr Georg Eckert / History

Photo: Mathias Kehren

The pen is mightier than the sword

The historian Georg Eckert on the resourceful and witty French power politician of the 17th century: Cardinal Richelieu

He was one of the most influential clerics of his time in France, and yet many people today know him primarily from the novel'The Three Musketeers' by Alexandre Dumas: Cardinal Richelieu. The Wuppertal historian Dr Georg Eckert has studied this extremely influential power politician of the 17th century and says: "Clerics of this rank had to be politicians at the time, and Dumas' 'Three Musketeers' also makes this clear. Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642) was one such politician, and an extremely successful one at that." He was appointed Duc de Richelieu and Pair of France by King Louis XIII in 1629. Born Armand-Jean du Plessis, he came from long-established nobility. His father had already shown himself to be a reliable military man in royal service. "The career of Richelieu, his third-born son, however, began as an ecclesiastical one. He was already Bishop of Luçon (a title conferred on the family by King Henry III) in his early 20s. It was precisely in this role that Richelieu proved himself as a champion of the Counter-Reformation - much to the delight of King Louis XIII, who at the time had to defend himself against the Protestant Huguenots. Richelieu was quickly given important tasks and offices. From 1624, he was the monarch's most important advisor and minister and remained so until his death in 1642.

Richelieu's statesmanship

Although films of the 20th century like to portray the great French statesman as a dull and scheming power politician, this clearly disregards Richelieu's ambitions, emphasises Eckert. "The cardinal practised statecraft in a comprehensive sense, he cultivated an enormous ambition as an author, who even wrote a classic of state thinking that is still worth reading today in his 'Political Testament'," explains the historian and continues: "Richelieu was an almost manic collector of books and works of art, as well as a generous patron of various arts and artists. For him, political power and cultural and religious splendour were not contradictory, but rather intertwined: Baroque splendour was a manifestation of power. This can be seen, for example, in the marble bust of Richelieu in the Louvre, created, significantly, by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the great artist of the popes."

Cardinal Richelieu (painted by Philippe de Champaigne around 1633, National Gallery London) public domain

Successful favourite enables absolutism

Even during his lifetime, there were many contemporaries who did not favour Richelieu and downright hated him. Eckert comments: "Favourites, such as Richelieu was, inevitably have enemies, because someone always envies them their elevated position at the ruling court. His resolute policy of reform in church and state provoked considerable resistance from Huguenots and high nobles - some of whom were connected to each other. There were even several threatening uprisings, the consequent suppression of which ultimately made Louis XIV's absolutism possible." His bad reputation in this country was based precisely on his successes in power politics, as his intervention in France during the Thirty Years' War ultimately led to territorial gains in Alsace at the expense of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Even contemporaries complained about this.

The king and the cardinal

As a shrewd strategist, Richelieu secured the monarchy in France, reformed the country and appeared to be more powerful than the king. "Power is difficult to measure," says Eckert, "but Richelieu was soon indispensable to Louis XIII, as he had even brought about a reconciliation with the young king's mother, who had been banished in the meantime. On the other hand, the reverse was true to at least the same extent: Richelieu owed his prestige to the monarch. Both were sober enough politicians to recognise in the other a guarantor of their own supremacy. Richelieu's special authority virtually presupposed the establishment and preservation of the king's hegemony; a coup by a cardinal would have been difficult to imagine, as both the king and his leading minister knew - and that is precisely why Richelieu was able to remain leading minister for so long."

Bust: Cardinal Richelieu created by Gian Lorenzo Bernini 1640/41, CC BY 3.0

Europe's first spy network?

Richelieu monitored the correspondence of diplomats and politically suspicious persons with the so-called 'Cabinet Noir', which opened up insights into the secrets of private correspondence by vomiting and skilfully resealing government letters. In this context, some researchers speak of a secret service network in the earliest form of espionage. "Richelieu's politics have long been covered by all kinds of stories, none more powerful than the aforementioned Alexandre Dumas''The Three Musketeers' and many films inspired by it, which are teeming with spies," laughs Eckert and emphasises: "Associations with a secret service belong more to the Cold War era than the 17th century. But Richelieu did indeed cultivate a network. His resolute reform and foreign policy included a shrewd, systematic handling of information and also disinformation. This was captured quite well in the 19th century by the British author Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who put the famous quote into Richelieu's mouth in a play: 'The pen is mightier than the sword'."

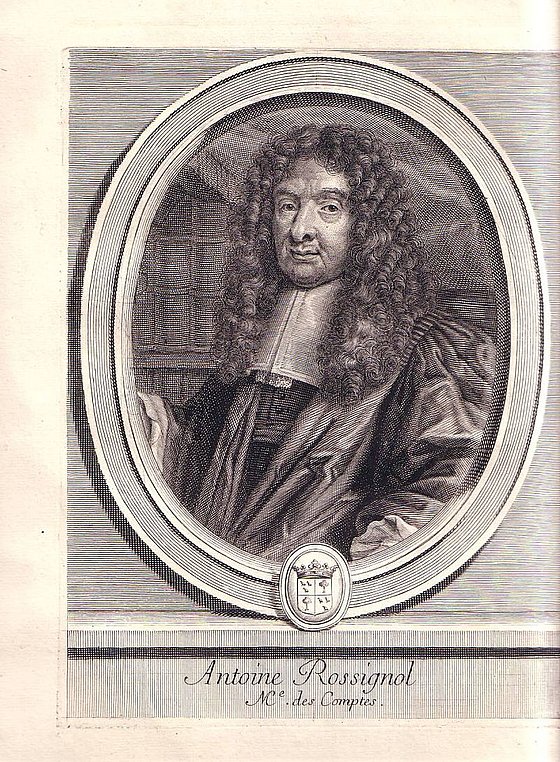

Antoine Rossignol, public domain

Richelieu and the mathematical code breaker

Encrypting messages was already part of the court strategy at the time, but was not a unique feature of Richelieu, emphasises Eckert, as encryption was already used in antiquity, and ancient Egyptian cryptography is even older. "Under early modern communication conditions, it was not to be expected that sensitive mail would remain untouched by the enemy, especially in times of military unrest." The mathematician Antoine Rossignol (1600 - 1682), who specialised in statistical methods for deciphering coded messages, performed an extremely important service for the French king by deciphering a cry for help from the Huguenots in a particularly spectacular case during a siege in 1626. He also created the 'Grand Cipher', a code that was considered unbreakable until the 19th century. "In this respect, Rossignol is less a French than a late humanist or early baroque phenomenon. His advice on decryption and encryption was based on an elaborate method that Richelieu appreciated with both political and scholarly instinct. In fact, the Huguenot Réalmont capitulated in 1626 when its commander was presented with a successfully deciphered letter - in which the besieged had discussed the end of their supplies."

Francois-Joseph Le Clerc du Tremblay, called Père Joseph, public domain

Confessor and information provider

Another of Richelieu's helpers was Père Joseph (1577 - 1638), the cardinal's confessor, whose speciality was spying on secrets at home and abroad, especially through religious brothers and missionaries. He also helped build Richelieu's network. "The system can be understood more as an early warning system than as a sinister secret service," the historian concludes, "once again, we should be wary of modern associations of a spy network with many technical refinements. It cannot be quantified, but its special quality can be recognised. Père Joseph was a broker of information. On the one hand, he collected it, especially through his contacts in the Capuchin order, from whose habit the 'grey' eminence is derived. On the other hand, he scattered information, for example by distributing it via the 'Mercure français'(a French-language journal of the late 17th and early 18th century, editor's note). Incidentally, we should also be wary of the assumption that the confessor whispered all sorts of things to Richelieu - it was nevertheless cultivated with pleasure, because in this way many concerns and interests could be discreetly brought to Richelieu's attention."

Richelieu's peace project

Many people do not realise that Richelieu conceived a peace project that some today would call a system of collective security. This means renouncing aggressive war in favour of a system of alliances in which all partners commit themselves to peace and take action against all peace-breakers. The most important thing, however, is that negotiations are held before a war and attempts are made to bring about a peaceful solution. Only if the aggressor cannot be brought to heel does the alliance have the right to take action against him. Eckert comments: "Richelieu's 'peace project' had the minor flaw that it was based on a France that was as strong as possible. What may look like a system of collective security to some today, in the context of the time simply meant that France was ideally bracketed between the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs. In other words: under French hegemony, smaller states in Europe were welcome to have equal rights as long as they did not jeopardise them. Richelieu was certainly not a suitable role model for a peace politician. He considerably prolonged and intensified the Thirty Years' War, first by making payments to Sweden as a belligerent and then by directly entering the war. France was also involved in the War of the Mantuan Succession (1628-1631) and attacked Spain."

A power politician par excellence

"The best secret service is the one that nobody knows", Richelieu once said. An obituary for him reads: "He did too much good for me to speak ill of him . Too much evil to be able to praise him". In France, at any rate, he is still present. "One site of the French National Library bears the cardinal's name and thus refers to the connection between power and art," says Eckert, "there is also a street and metro station in Paris named after Richelieu. This indicates a still common association of the statesman with French greatness, both political and cultural. This is precisely why Richelieu is also an excellent villain in more than a few films - and even more so in the memory of the Huguenots he fought against. For obvious reasons, Richelieu did not become a patron saint of the EU. He was an extremely resourceful and witty power politician, but a power politician. That doesn't usually go down very well today."

Uwe Blass

Dr Georg Eckert studied history and philosophy in Tübingen, where he completed his doctorate with a study on the early Enlightenment around 1700 with a British focus, and habilitated in Wuppertal. He began working as a research assistant in history in 2009 and now teaches as a private lecturer in modern history.