Authorisation procedures in the construction industry

Alexia Radounikli, Prof' in Dr.-Ing. Tanja Siems and Dipl.-Ing. Mohamed Fezazi / Architecture

Photo: UniService Transfer

Authorisation procedure: Logic versus pragmatism

Professor Tanja Siems and her team, architects Alexia Radounikli and Mohamed Fezazi from the Department of Urban Design at the University of Wuppertal, on the lengthy administrative processes involved in building approval procedures

Whether it is a new building, a roof extension, an additional garage or the change of use of a building, everything requires an authorisation procedure. Many planners and builders, but also citizens, who start such an endeavour for private or commercial buildings experience that the wheels of bureaucracy move quite slowly and bring projects to a standstill very often. A constant stream of new guidelines, which are sometimes incomprehensible, make work more difficult. If, for example, a city or municipality wants to build something, it usually has to put the contract out to public tender throughout Germany. However, if the planning services of architects, engineers and technicians each exceed a threshold value of 215,000 euros, tenders must even be invited throughout Europe. The federal Government also supports this procedure.. However, it means a considerable amount of extra work and significant additional costs for the client.

Professor Tanja Siems from the Department of Urban Planning says, "Functioning urban structures always consist of a balanced coexistence, cultural vitality, a conscious approach to the immediate environment and its resources, as well as social justice and economic prosperity." Therefore, the question arises whether construction projects that are put out to tender across Europe do not stand in the way of this idea.

Siems has a very clear opinion on this issue: "An Italian office, for example, would not even apply for this volume, as they would immediately have to set up a branch office in Germany and bring everything necessary for the construction process with them. That would be far too costly and not commercially viable. It might look different with regard to a co-operation," continues the urban planner. "We developed an urban planning and infrastructure project for Brussels, in which we worked together with colleagues from various disciplines from the past. They approached us because our office has the expertise in the disciplines of architecture, urban planning and transport design that they needed in Brussels for the tender. However, that only works if you absolutely trust each other. You would never co-operate in such tenders with a partner with whom you had not previously worked intensively – and that doesn't depend on the budget."

Such tenders, as the German government would like to see, therefore appear to be just wishful thinking.

Europe-wide tenders mostly in the national language

Mohamed Fezazi, a member of staff at the chair, cites an example that shows how the procedure works in European architecture competitions. "In the Europe-wide architectural competitions, there are regulations that stipulate that the designs can only be submitted in the national language. This means that if a German office wants to take part in a Finnish competition, they are usually in a bad position. As long as these obstacles exist, you're really only talking about a façade." Although Germany writes many tenders in English, Siems adds, you need business partners who have a good command of the language, especially when it comes to technical execution. "It also has to be said that large firms are more likely to be able to handle such extensive projects. Smaller architectural firms usually don't have the confidence to do this in another European country because the workload is too high." This situation shows a very strong imbalance between large and small companies.

Large agencies enjoy advantages when you have to react quickly

Complex EU tenders are a huge problem for regional companies and therefore they lose many public sector contracts. The municipality of Ahrweiler is a current example of how slowly reconstruction is progressing after the flood disaster in the Ahr valley, says Fezazi. "They have big problems when they have to put certain services out to tender at great expense, because it's an incredible bureaucratic effort and construction times are extremely long. It's an organisational problem, but it's spreading economically to the offices." The large offices usually receive the contracts directly because they have already carried out similar projects, explains Siems. "Young, planning and executing offices have no chance at all, unless they can already present a larger portfolio through networks."

Italy and France show what is not possible in Germany

In Italy, following the collapse of the Morandi Bridge in Genoa in 2018, the new San Giorgio Bridge was completed on the same site within two years. The Rahmede Bridge in Lüdenscheid was closed in 2021, blown up in 2023 and is not expected to be completed until 2026. Long approval procedures also mean that local companies are building abroad. The Wuppertal-based company Vorwerk, for example, is building a second Thermomix plant in France and clearly is speaking of the favourable conditions for industry in France. However, migrating industries also weaken our cities. "Energy prices are breaking everyone's neck in the construction industry at the moment," says Radounikli. "They are the biggest cost factor, which is why German locations that actually operate internationally are posting negative figures."

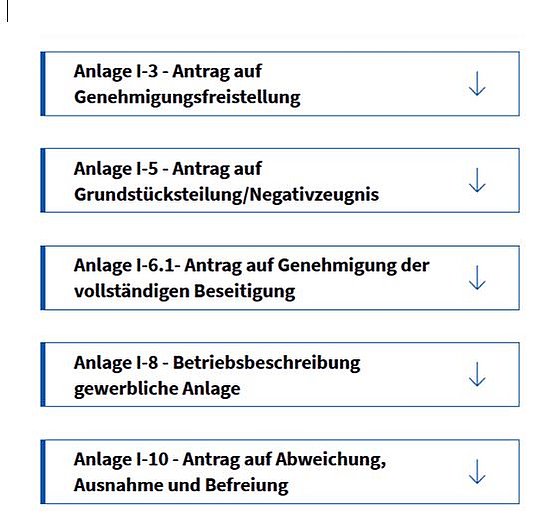

Extract from: Building application forms for the Building Regulations for the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (BauO NRW)

Authorisation procedures take half a year too long on average

The Federation of German Industries (BDI) has analysed 250 procedures from 27 sectors over the last five years and says that Planning and approval procedures would take half a year too long on average. Authorities are permanently overloaded and are considered by industry to be inefficient. Take Poststraße in Wuppertal, for example: the main axis from the railway station is an imposition for all visitors to the city and will not be ready for construction until the end of 2024. Yet the necessary steps seem clear: standardised procedures for more legal certainty, better staffing of the authorities and courts and an amendment to various European environmental directives and regulations. What makes laypeople despair is seen more calmly by experts. "The problem is that you see too many of these waiting situations and know where the problems lie," explains Radounikli. "When you enter this industry at the end of your studies, you know that this situation is permanent and you experience it as normality. In other words, professionals react calmly to this situation whereas the people living the city are horrified. "

In this context, Fezazi asks questions such as "Why aren't there experts for commercial buildings and experts for residential buildings in the building authority? Why doesn't the simplified building procedure apply to more building classes? Why is there no case manager for better processes in the authorisation phase? Why do normal cases immediately require a fire safety expert, and why do all these questions have to go back and forth at so many points in the administration until they can be approved?" For him, one thing is certain: "All these procedures could be handled more quickly."

No architect is needed for a change of use application

In the German application jungle, it is no longer possible to distinguish between individual forms. "The form for a change of use application, for example, is exactly the same as a planning application," Radounikli says. This procedure is identical in most local authorities and users ask themselves why it is necessary to commission an architect for a change of use application. It is not a matter of a new substance, as the documentation of the building construction is already registered and therefore the building control department can inspect the building. "Only the new use needs to be checked, but this is an organisational check and could be significantly accelerated," says the architect.

Cities need to open themselves for new concepts

In May 2023, the German business newspaper Handelsblatt spoke of increasing problems in the construction sector. The major housing associations even saw new construction in Germany on the verge of collapse. Siems has published a book entitled "Stadt vermitteln - Methoden und Werkzeuge für gemeinschaftliches Planen" (Communicating the city - methods and tools for collaborative planning) in which she points out new approaches. "Networking is an important part of urban planning processes. You have to rework strategies and concept ideas with regard to structures and materials and involve initiatives and stakeholders at an early stage," she says. You have to be open to an intensive dialogue with experts and city stakeholders at all times. The flexible thinking of all those involved must be encouraged. "You need like-minded people. In our multidisciplinary project in Brussels, it was very helpful that we had the traffic engineers, landscape architects and safety engineers on our side right from the start thanks to our mediating methods within the planning process. If the main person in charge thinks flexibly and works openly, it is no problem to implement complex systems. On the current and controversial topic of AI, when artificial intelligence is used within planning and construction processes in the future, we will still need individual people as decision-makers. Experienced architects and planners always have a sense of whether something works or not."

Approval procedures lag behind the times

Long approval procedures are also detrimental to climate change, because an effective climate transition also requires upgraded railway lines, modernised roads for electric cars and functioning bridges. With the current regulations, it often takes more than 10 years from the idea to the construction of these infrastructure projects. "Yes," confirms Siems, "but this is because we are building on the old principles. One example of this is e-mobility; you would need a completely different infrastructure, the whole city would have to change structurally in a very short space of time. There are many good and constructive ideas, but they are often stopped because systems change too slowly."

Approval procedures are also only one aspect of the many factors that determine our living space, explains Fezazi, as discussions with young students always lead to new ideas that solve old problems. "The students are sensitised for how something like this can develop. A city is a highly complex topic."

At the end of each semester, Siems therefore repeatedly invites experts and laypeople and gives the students the opportunity to present their results.

Informal planning is a creative process without limits

"Building law requires formal planning, which is clear and explains what can be placed where and how. On the other hand, there is informal planning," says Radounikli, "and here we have almost complete freedom and can be creative. That is the driving force, the creative process, to which there are no limits. Everything that goes into this informal planning from citizens' initiatives, workshops and event formats must have the same seriousness as the formal planning".

"In the time it takes to develop something, something is already being created," adds Siems. "I have to take that just as seriously as the final product. Think small and flexibly so that I can also change it."

There are plenty of urban development opportunities for the future; it is no longer just about the masterplan, which absolutely has to be implemented, concludes the urban planner. Many small steps in between are important and that is what she shows her students on their way to a career.

At the beginning of all projects, creativity always comes first. However, good strategies and concepts must also be recognised so that outdated rules can be changed.

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Tanja Siems is head of the Chair of Urban Design at the University of Wuppertal.

Alexia Radounikli (M.SC) is pursuing her doctorate at the Chair of Urban Design.

Dipl.-Ing. Mohamed Fezazi is an architect and research assistant at the Chair of Urban Design.