The German language through the ages

Prof Dr Svetlana Petrova / German Studies

Photo Petrova: Maren Wagner

The German language through the ages

Prof Dr Svetlana Petrova from the University of Wuppertal on the changing development of the German language over the centuries

Mrs Petrova, our language is subject to constant change. You are Professor of Historical Linguistics of German at the University of Wuppertal. How do we recognise change in the language today and over what period of time does it happen?

Petrova: Change affects various levels of linguistic representation, from phonetics and the structure of words to word order and vocabulary. The corresponding processes take place at different times and are not recognisable to us in the same way. Some changes take place before our eyes; others are very long in the past. We recognise change most clearly, when we compare words and structures from texts of different language levels. This requires knowledge that enables us to understand the linguistic evidence on the one hand and provides us with the necessary analytical tools on the other. We impart this knowledge to our students at university. Irrespective of this, the language community itself has a feeling for changes in its linguistic environment. The most obvious changes for us are in the area of vocabulary. The word lateral thinker, which the University of Wuppertal used to advertise before the COVID-19 pandemic, no longer has a positive connotation. Its meaning has deteriorated. We recognise this change ourselves and use this word according to its new meaning. The word has disappeared from the University of Wuppertal's poster advertising.

The most controversial area of change in language is definitely the introduction of words from other languages. Interestingly, no one discusses words such as wine and wall, which were once borrowed as foreign words and are now fully adapted to the German system. There is also little public discussion about the French loan words uncle and aunt, which have replaced the native terms cousin, uncle, base and mum. Currently, the focus is on the numerous words from English that our language is adopting in connection with globalisation, the use of social networks or the establishment of new information technologies. However, these words are also being adapted to the German system. The vocabulary changes, but not the system as such: the underlying principles of German are retained and systematically applied. For verbs such as chill, we create forms like ich chille or wir haben gechillt, for user and blogger there are forms e.g. von vielen Usern und Bloggern, we use these words as the basis for new terms such as chillig, Userin, Influencerin, etc., which do not exist in the source language. At the same time, we have moved away from Anglicisms such as walkman and are in the process of saying goodbye to twitter. That is also change. New terms are constantly being created, whether by adopting them from other languages or by using our own language, e.g. Strompreisbremse and Waffenverbotszone. We use the terms to name new objects or phenomena, or we look for more expressive, explicit or memorable forms for existing terms.

Since when has there actually been a German language?

Petrova: The first surviving records of the German vernacular langiage date from around 800, which are translations of Christian texts from Latin, single-word records and the first free poetry. However, we cannot speak of a standardised German language at this time. They were written in any dialect. There was no supra-regional standard. The word German was used in the earliest period to distinguish the vernacular from Latin, the main medium of written communication. German originally meant 'written in the indigenous language.

German belongs to the Indo-European language family. What does that mean?

Petrova: German is a representative of the Germanic group within the Indo-European language family. This means that German is closely or distantly related to a large number of languages that have been spoken from the Indian subcontinent in the east, across the Near East and throughout Europe to the island of Iceland in the north-west and are still spoken today. In the 19th century, while studying Sanskrit, the language of ancient Indian scholars, it was realised that it was similar to the well-known ancient languages of Greek and Latin in terms of sound, vocabulary and structure. It was assumed that the similarity was not due to coincidence, but to the splitting off of the individual languages from a supposedly common basic language, which was called Indo-European. This was followed by an intensive examination of the languages in Europe and the Near East, whether still living or no longer spoken, which established the relationship between many languages. Today we know that German is not only related to other Germanic languages such as English, Dutch or Yiddish, but also more distantly to the Romance and Slavic languages, as well as to languages such as Armenian, Albanian and Greek, Persian in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, Hindi in India, Urdu in Pakistan and many more.

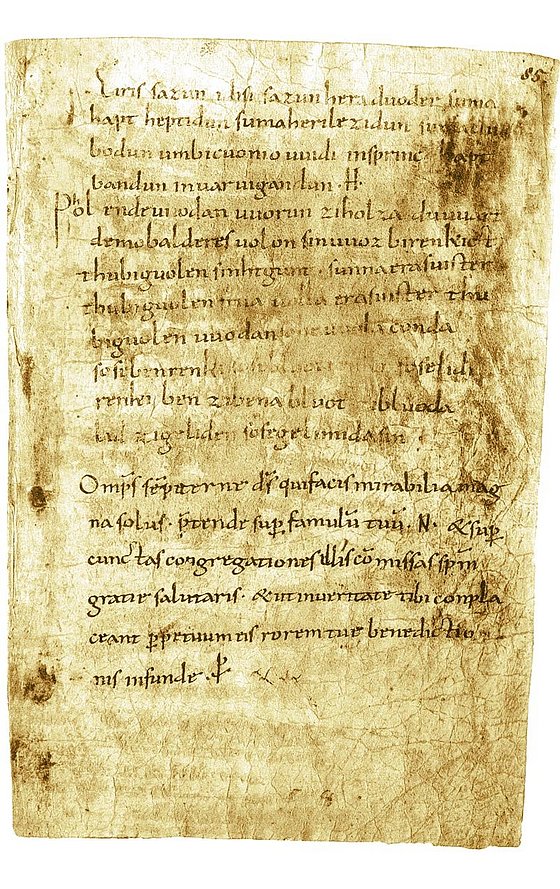

Merseburg spells

Colour image from Cod. 136, folio 85r, Merseburg Cathedral Abbey Library, public domain

The Merseburg charms were among the first surviving Old High German texts. What is this all about?

Petrova: This chronological categorisation is not entirely correct. The genre of spells itself is old, even pre-literary, a type of short-form poetry that was widespread in pagan Germanic regions and was used as a performative speech formula or as a written wish formula to give effect to an action. This is why this genre has the magic of the miraculous, the secretly incantatory and the magically performative. The so-called "Merseburg Charms", 2 poems found in a composite manuscript in the library of the cathedral chapter of Merseburg, date from the first half of the 10th century and are therefore somewhat younger than other written evidence from the Old High German period. Like spells themselves, they contain a short epic part that tells a story and then the actual spell, a kind of formula that is intended to be used as a release spell to free prisoners from their shackles or as a healing spell to heal a horse's dislocated foot. Modern equivalents of the spells include the children's spell Simsalabim or expecto patronum in "Harry Potter".

Much has changed from the Old High German language (around 700 AD), through the Middle High German language (up to 1350 AD) to the Early New High German language (from 1350 AD) to the New High German language (from 1650 AD), which continues to this day. What drastic upheavals can you name?

Petrova: It's a very long period of time in which a lot has changed in the language. I'll use an example from my own research to illustrate this. Modern German uses the periphrasis werden + infinitive to refer to pending events. Today, when saying goodbye to a loved one, I can say: I will miss you, without any uncertainty or doubt about the sincerity of my feelings. This construction denotes what, in my view, applies in a time after the time of utterance. Werden + infinitive, however, can only be proven with certainty in the 14th century and took centuries to assert itself against competing forms. These included constructions with the modal verbs wollen and sollen, which survived as future constructions in other Germanic languages, such as will/shall with infinitive in English and zullen with infinitive in Dutch. Together with my colleague Elzbieta Adamczyk from the English Department at the University of Wuppertal and other researchers from Cologne, Mainz, Würzburg and Jena, we want to focus on the development of forms for expressing pending events in Indo-European. Other areas include the emergence of the article system, the enormously broad range of phonology and the sharpening of the distinction between singular and plural nouns. Verbs have changed their selective properties, so that instead of a thing needing or forgetting we now say a thing needing or forgetting, i.e. replacing the genitive of the object with the accusative, or more recently replacing the genitive in gedenken eines Verstorbenen with the dative, i.e. gedenken einem Verstorbenen. However, some things also remain stable over a very long period.

For example, if a merchant from Hamburg wanted to do business in Nuremberg in the 15th century, he would have needed an interpreter. What did people who didn't speak Latin do in such a case, i.e. how did communication actually work in the Middle Ages?

Petrova: It is true that for a long time, there was no nationally recognised variety of German and that the various dialects and dialects differed greatly from one another (as is also the case today, as they have not disappeared but continue to exist alongside the standard variety). People at the time were aware of the linguistic heterogeneity in the German-speaking world, and it is often thematised in written documents. However, it was customary for merchants, who were not resident until the 13th century, but travelled for long periods of the year, to be multilingual. Furthermore, in the course of the administrative system, office and writing languages emerged, which replaced Latin with a dialect typical of the region and, depending on their degree of effectiveness, were used nationwide as lingua franca, e.g. in trade. For example, from the 14th century onwards, the written language of the Lübeck Chancellery was the common lingua franca of the Hanseatic League, not Latin. The official languages of other chancelleries also emerged as prestigious variants at different times and were used more widely in different areas. For example, the language of the Maximilian Chancellery, a southern Bavarian variant from the late 15th century, had a major influence as an administrative language throughout southern Germany, also known as "common German". The language of the Electoral Saxon Chancellery also had a great influence, especially in the Protestant area, not least due to the writings of the reformer Martin Luther, who used this language in the chancellery. With the flourishing of towns and trade, correspondence increased significantly in size and importance. Municipal and public schools were established in which writing was taught in the native language. Merchants were generally able to read, write and do arithmetic. It is said that this broke the clergy's monopoly on education.

There were also so-called "Trutschelmänner" in many towns. What did they do?

Petrova: Trutschelmänner, also known as Trutzelmänner, were actually interpreters who spoke many languages and originally accompanied travellers and pilgrims on their journeys. This use is supported by the fact that the word is considered an Arabic loanword.

Parts of the old language and their meanings have been forgotten over time. How do you reconstruct these texts?

Petrova: When it is a question of attested words falling out of use or taking on new meanings, which is why the original meaning and the history of meaning should be determined, the contexts and the distribution of the words in the older sources are analysed, also in comparison with related languages. This knowledge is recorded in etymological dictionaries, which are also available digitally today. There is also other evidence about the original meaning of words: billig, for example, originally meant 'permitted' and later took on the meaning 'inexpensive, inexpensive'. It is related to the verb billigen, which has the original meaning 'to allow' to this day. In words such as Eigentum, Eigenheit, eigentlich etc., the lost root word ahd. eigan lives on, which meant 'to have, to possess'; similarly, an unattested infinitive of the verb sein, mhd. wesen, lives on in Wesen und wesentlich. There are many more examples of this kind. Sometimes it helps to compare languages: in Middle High German, turren still meant 'to dare', which is related to English dare with the same meaning.

AI speaks letters

Photo: Pixabay

It is said that language is subject to constant change. What factors are responsible for this?

Petrova: The most important factor in change is language economy, i.e. the common pursuit of minimising effort, but not at the expense of communicative goals. The maximum maxim, as Rudi Keller puts it, is to achieve your communicative objectives as successfully as possible with as little effort as possible. Another factor in change is language variation, the immanent coexistence of forms and expressions that characterise language use in different contexts, such as communication in social groups or in different discourse situations. Social groups develop varieties (linguistic variants, editor's note) as a means of demarcation in a positive sense - the use of the variety is serving identity development for the members of this social group. This applies equally to youth language varieties and technical jargon. Finally, language contact is a factor in change: languages adopt the structures of their contact languages or try to imitate them with their own means.

Ms Petrova, where do you think the German language is heading in times of digitalisation?

Petrova: Even in times of digitalisation, language will remain the main medium of communication. Language is not becoming superfluous. Human-machine communication and the use of digital formats for transferring content are language-based. I even see advantages associated with the fact that machine language processing, for example in communication with chatbots etc., requires linguistic precision and coherence in the formulation of prompts (prompts are short notes, editor's note) and thus even improves the skilful use of linguistic formulations and the structure of sequences.

Many people associate the changes brought about by digitalisation with the massive introduction of words from the English language, such as chatbot and prompt. However, these expressions are adapted very quickly and efficiently to the German system, and such words can also disappear at some point, such as the Anglicisms walkman and twitter.

As far as the role of social networks in language change is concerned, I would like to say the following: language in social networks is often criticised as language decay due to its deviation from standardised spelling, but also due to its proximity to orality, colloquial language and group-specific registers. The application of official rules is only binding for school and administration, but not for private communication, and how I appear in private correspondence and informal communication says little about how I have mastered the grammatical rules of the written language. Language teaching has been moving away from the absolute dominance of standard language and writing in favour of the linguistic heterogeneity of authentic communication since the 1970s. There is nothing wrong or strange about users making use of expressions that identify them as members of a particular group or creating expressions with which they want to be more expressive, more perceptible and therefore more successful in their communication. There are other areas pursue their own communicative goals in the same way when they say DB lounge instead of waiting room or job centre instead of employment office.

In principle, a language remains the same as long as it is acquired and used by speakers as a first or second language. Digitalisation will not change this.

Uwe Blass

Dr Svetlana Petrova has been a professor of Historical Linguistics of German at the University of Wuppertal since 2011.