Apocrypha - Hidden Scriptures

Prof Dr Kurt Erlemann / Protestant Theology

Photo: Sebastian Jarych

Apocrypha - Hidden Scriptures

Theologian Kurt Erlemann on religious texts that did not find their way into the Bible

In 1947, the religious world held its breath for a short time when the so-called Qumran Scrolls were discovered at the Dead Sea. They are considered the archaeological sensation of the 20th century, as the texts on them cover a period from the third century BC to the first century AD and shed new light on the Bible. By 1956, around 1000 scrolls had been discovered in up to 15000 fragments. The Qumran texts include some of the oldest known Bible manuscripts, but also so-called apocrypha, i.e. writings that were not later included in the official biblical canon. "Apocrypha are literally 'hidden scriptures," says Kurt Erlemann, professor of New Testament and History of the Early Church at the University of Wuppertal, "which are not actually part of the canon of the Holy Scriptures (the canon of the Holy Scriptures is the list of writings that Judaism and Christianity have defined as part of their Bible, editor's note), but are, so to speak, 'writings in the second row'."

Apocrypha are not in the Bible

Apocrypha are not in the Bible. "This is not quite true," Erlemann qualifies, "because the Apocrypha are definitely printed in the Luther Bible, at least they are included as an appendix in the large editions. It then says: Apocrypha. This refers to writings of the Old Testament that were added late to the Old Testament and where one can argue about whether they should be given the same status as the other Holy Scriptures." As examples, he cites writings such as the Book of Jesus Sirach, the Book of Judith or the Book of the Wisdom of Solomon. The way in which these stories found their way into the Luther Bible is interesting. "They were originally in the Septuagint (the Septuagint is the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament, editor's note) and from there they came into the Latin translation, the Vulgate. From there, in turn, they found their way into the Catholic Bibles, so that they were no longer labelled as apocrypha, second-order writings. Luther did not refer to the Septuagint and the Vulgate, but to the Hebrew Bible of the Old Testament. And these apocryphal writings are not yet included there." Luther took them over anyway, but then wrote: second-order writings, apocrypha. That is the difference between the Catholic and Protestant editions of the text, because the Catholics cannot see what the 'second-order writings' are.

Findings about early Judaism in the Qumran scrolls

Among the Qumran manuscripts is the Temple Scroll, which covers a period from 53 BC to 21 CE and may offer new insights for religious studies. "What these manuscripts definitely enrich is our knowledge of early Judaism," explains the theologian. "Beyond the canonical texts, there were also other writings that were developed and passed on. There were Jewish groups that may have distanced themselves from Jerusalem and the cultic centre, the temple, because they did not feel represented there. The Qumran people had their library at the Dead Sea. Some of these were canonical writings from the Old Testament, such as a scroll of Isaiah. But there were also writings that were specifically intended for this community, for example a community rule, a temple scroll and much more." These scrolls show us today that Judaism was by no means uniform at the time of Jesus. "There were umpteen different groups. In the New Testament alone, we don't just know of Pharisees, there are also Sadducees, Zealots and Sicarii. We know from Josephus about the Essenes, there were apocalyptic groups, there were Asideans etc., i.e. more or less conservative Jewish groups ranging from highly political to apolitical. With the finds from Qumran, we have texts from the time of Jesus that show us that there were Jewish groups that sometimes thought similarly to Jesus, but also completely differently."

Jesus' childhood in the apocrypha

In the Bible, we lack any information about Jesus' childhood, except for an episode in a temple in Jerusalem, where the 12-year-old Jesus impresses the scribes with his understanding. However, the Apocrypha does provide childhood stories. "You have to differentiate between the historical and theological significance, because these stories fuelled popular piety and also came from the needs of popular piety. People simply wanted to know something about the young Jesus and many legends developed that testified to the divinity of the boy Jesus from the very first year of his life." Only one to three years of Jesus' life are depicted in the Gospels. The thirty years before that are somewhere in the dark, and popular piety wants to know how this boy grew up and what great things he had already done before he appeared in public. "The theological relevance is rather low because we know it's not very authentic," says Erlemann, "we have what we need for faith in the Gospels. What's more, the stories are sometimes quite weird," laughs the theologian, "Jesus casts a spell on his teacher or saves a fellow pupil who has fallen off a flat roof while playing with him. They are not important for theology."

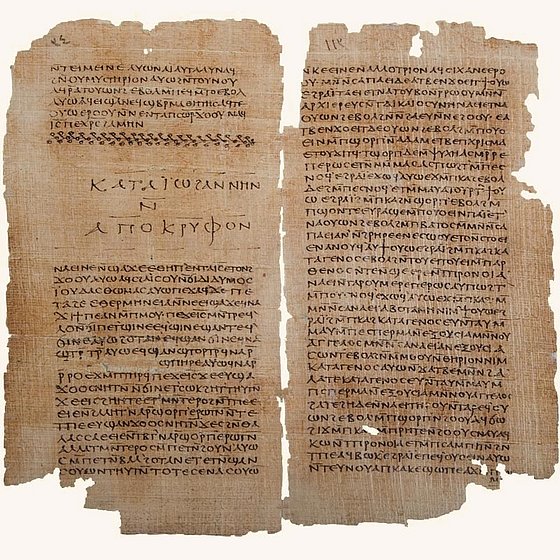

Apocryphon of John:

The left-hand papyrus leaf shows the title in the signature (subscriptio) of the

Apocryphon of John in Nag Hammadi Codex II. Below it begins the

Gospel of Thomas

Photo: public domain

Old Testament apocrypha are well researched

When talking about apocrypha, it is first necessary to differentiate again, because a narrow concept of apocrypha as a text corpus refers to the Old Testament writings that were written between the third and first centuries BC, explains Erlemann "They are explicitly called apocrypha or second-order writings. This term is also used for all kinds of early Jewish and early Christian texts that never ended up in any edition of the Bible, but which are also categorised as apocryphal. One could include the Qumran scrolls or the unwritten words of Jesus (Agrapha) as well as apocryphal gospels, apocryphal letters of the apostles, apocryphal apocalypses, etc." The Old Testament apocrypha have all been very well researched and are available in different editions. "Nothing is stashed away in the Vatican or under lock and key because it could undermine the faith," Erlemann clarifies, "they can all be read and studied."

40 to 50 gospel-like texts are still known today

Outside of the New Testament, around 40 to 50 gospel-like texts are known today, from antiquity alone. There are only four gospels in the New Testament. "Yes, that was a long process that took several centuries. You can't say that there was one person, one authority or one council that decided this. It was rather the case that the writings, such as those of St Paul or the Gospels, were handed down in the churches and used in worship. There were writings that wore out quite quickly after their first use because they were focussed on a very specific issue that was once important in a generation or region, but later no longer played a role. Other writings have stood the test of time over the generations because they offered potential solutions for issues that went far beyond the first generation." These writings became established in worship and were able to distinguish themselves from others as holy writings over time. "There were also theological and historical criteria," explains Erlemann, "some writings were assigned to an apostle or a disciple of an apostle." The theological classification was then about recognising what was to be considered legitimate or legendary. "This process began in the middle of the second century, when a Gnostic named Markion began to compile a first canon, i.e. a guideline of sacred writings. This canon was decidedly anti-Jewish. There was a Gospel of Luke purged of Jewish ideas and censored letters of St Paul. He did not even consider the other Gospels. The Old Testament also played no role for Markion and the Gnostics from a theological perspective." This in turn provoked church fathers to develop their own canon over time, with a clear commitment to the Jewish heritage, which they also had in the New Testament and in Christianity. At the beginning of the second century, there was an initial compilation, the Canon Muratori, which in principle contained the four Gospels, the letters of St Paul and a few other writings. However, the process continued well into the fourth century. "It wasn't until the middle of the fourth century that we started talking about the Old and New Testaments. The term 'canon of the Holy Scriptures' was then first defined by Athanasius, the great church father, in 367 AD." To this day, the canon is still different; it has never been completely standardised in the Eastern and Western churches.

The apocryphal story of the ox and the donkey

Nevertheless, some of the 'second-order writings' have been handed down to this day. For example, the idea of the Magi, the image of the ox and donkey at the manger and depictions of the true face of Jesus or the accompaniment of Jesus to Golgotha by St Veronica originate from the apocrypha. "The same applies here to the Infancy Gospels," adds Erlemann, "they have become very important for popular piety. Popular piety always tried to preserve such headline-grabbing things. Everyone knows the Shroud of Turin, people also wanted to have something tangible in their hands as a connection to Jesus. That was and still is important to people today. People have always tried to collect and search for relics of saints, whether they were drops of Jesus' blood or scraps of a robe. It started very early on. But it hardly plays a role in the Protestant world." The theologian confirms that the story of the ox and the donkey is not actually included in the Gospels. "We have the formation of legends from the fourth century onwards, but it first becomes tangible in literature in the sixth century in the Pseudo Gospel of Matthew, also an apocryphal gospel, where the ox and donkey are mentioned at the manger, with reference to Isaiah 1:3." However, this mention was very anti-Jewish because the text says: "Every ox and every donkey recognises the manger of its master, only you, the people of Israel, do not recognise him.

We can learn from the Apocrypha

"In terms of religious history and theology, we can learn a lot from the Apocrypha," says Erlemann, "we can get an even sharper view of the canonical scriptures' own profile by seeing what was considered canonical and what was not. We can also see that it is a very small section of the early Christian writing tradition, because there was a lot of literature in early Judaism and early Christianity. Only a minimal percentage of this was later included in the canon of the Holy Scriptures. This somewhat relativises the image we have of early Christianity. With the Apocrypha, we suddenly see the richness of literary formation and theological thought, including community types that we do not find represented in this way in the canonical writings. The Apocrypha reveal the richness of early Christianity."

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Kurt Erlemann holds the Chair of New Testament and History of the Early Church at the University of Wuppertal.