The Norwegian timber house

Prof. Dr.-Ing. Christoph Grafe / History and Theory of Architecture

Photo: UniService Transfer

The Norwegian timber house and the search for traditional building materials

Christoph Grafe on Wuppertal's first prefabricated house and the history of timber construction

In 1516, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) described his plan to build an ideal city on the Loire consisting exclusively of demountable type houses. Although this idea was never realised, it shows how early architects were already thinking about movable dwellings. A very early example of a demountable prefabricated house can be found in Wuppertal at Kohlstrasse 64, a building known as the Norwegian Timber House, which the Wuppertal Monument Authority considers to be an important building in the history of architecture. Christoph Grafe, who works as an architect at the University of Wuppertal, knows more about the history and future of mobile timber construction.

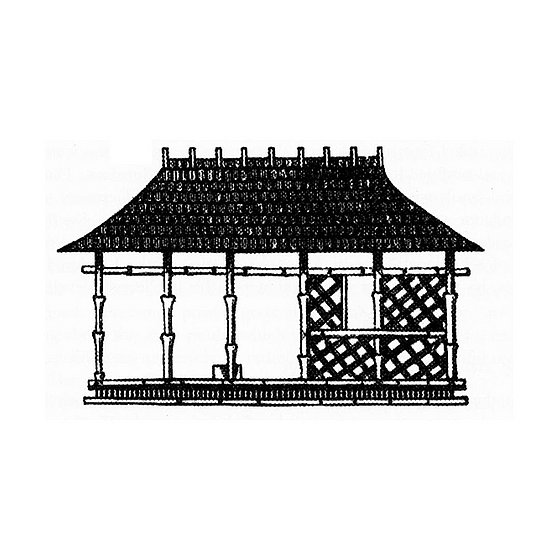

Caribbean Hut

Caribbean Hut, Gottfried Semper, The Great Exhibition of 1851, London, drawings by Der Stil, 1863

The Caribbean hut as a model

"The Norwegian Timber House has a very interesting history," he begins. "It was initially built and erected for the 1900 Paris Exhibition. Then the banker August Freiherr von der Heydt bought it. The house was then transported by railway and reassembled in Wuppertal." Although the Norwegian Timber House was not the only timber house in Paris at the time, other buildings were also sold to various countries; it is certainly the only prefabricated house from the World Exhibition that is still standing in Wuppertal today. However, the success story of these buildings begins with the 1851 World's Fair in London. "The mother of all world exhibitions in London, the Great Exhibition of 1851, showcased the latest technical developments and also brought together everything that existed in the world," explains Grafe. "One aspect of this was that a so-called Caribbean hut was built in London in 1851. It was a very simple construction made of wood, but it was very important for the history of architecture because for the first time an ethnological aspect and the tradition of building by peoples outside Europe or rural regions in Europe were part of the exhibition." In addition to technological innovations, the experts were also looking for traditional building forms. "Gottfried Semper, one of the most important architectural theorists of the 19th century, formulated new aspects of architectural theory based on these experiences with the Caribbean Hut. This vernacular architecture, whether European or not, is taken up and there is an interest in its construction methods."

The industrial revolution discovers timber construction

Even during the industrial revolution, architecture was orientated towards lightweight construction. Interest in mass production grew and people were inspired by traditional construction methods. "At the same time, there was already a tradition of so-called timber frame construction (balloon frame) in North America. This is a timber construction method that is highly industrialised and consists of very few individual elements," explains the expert. "It is a frame that operates with absolutely standardised sizes. It can be built very quickly and does not require valuable timber, but can work with timber that is available in large quantities. This is a building activity that is completely normal in North America, where you rarely find stone houses." In Scandinavia, too, wood has always played an important role in everyday architecture, explains Grafe. "There was an abundance of wood as a building material. The only natural stone available there would have been granite, which you generally can't build with. We also know this from films about Sweden and Norway. Denmark is not one of them, because they use traditional brickwork. In the densely wooded areas of Scandinavia, timber houses were the norm. Even for larger construction projects, people use wood."

The growing house

Although many workers' housing estates with standardised houses had already been built in the 19th century to cope with the housing shortage, the real breakthrough only came after the First World War. In 1931, the Berlin architect and urban planner Martin Wagner proposed the so-called Growing House, reports Grafe. "These are very simple, modern prefabricated houses, mainly made of wood. The background to this is that it was thought that the housing shortage could be alleviated by allowing people to build their own homes. With a prefabricated house, you need fewer specialised workers because things are prefabricated, similar to an Ikea package. Therefore, someone who hasn’t learnt how to use the assembly can also built the house. That was the idea of building on one's own initiative for labourers and goes hand in hand with the idea of building settlements. The house then stood on a plot of land where you could also grow your own food. That in turn was also linked to the idea of the garden city." It is particularly interesting with Wagner, because it is not called the Growing House for nothing. The house could also be extended. "This is a key aspect, namely that you can make something out of wooden components that can be adapted relatively easily. You can keep the house small at first, depending on your financial means or family situation, but you can also expand it if necessary."

Detached houses can create high density

However, building timber and prefabricated houses is not without difficulties in urban planning, as the concepts are generally based on detached single-family homes. "We currently have a tendency to build high-rise buildings made of wood, and there are a number of examples," says Grafe. "At the same time, there are studies of residential neighbourhoods that have a relatively high density, but do not necessarily go up in height." Grafe cites one example: "There is a series of self-build neighbourhoods in London by the architect Walter Segal, who originally came from Germany and also comes from this Wagnerian tradition. He planned self-build housing estates using wood with a maximum of two storeys. They are intelligent and densely nested, and the plots are not very large. This is achieved, for example, by centralising the parking and embedding it in the landscape, so these houses are now often intertwined with the trees around them. Sometimes they look like tree houses, which makes them incredibly idyllic. They take up very little space. This means that it is perfectly possible to build individual houses. There is also the example of small two-storey houses in Japan. Intelligent open space landscape planning and parcelling is necessary, as well as a certain degree of structuring so that privacy is not disturbed. Then you can also achieve a high density with a single house." Grafe was recently on site and looked at the former project. "It's really impressive. The houses are around 30 years old and the residents obviously dearly love them. The combination of a relatively high density and the very relaxed living that you can perceive is convincing." This project really creates an attractive living environment, the plot size is relatively limited, but at the same time, you can see that people have added verandas or conservatories, or an extra room in a way that would not have been possible with a stone house. "You can see that this is what people actually want: living in a detached house in privacy and freedom with design freedom, and that works particularly well in this type of construction."

Solar Decathlon Europe - building up instead of building new

The Solar Decathlon Europe (SDE) university competition came to Germany for the first time in 2022 and built on the site of the Mirk railway station. 18 teams from eleven countries qualified for the urban decathlon for sustainable building and living in Wuppertal. They planned, built and operated solar houses with a neutral and even positive energy balance. The SDE therefore had as its motto "Design - Build - Operate". Wood was also used at the competition as one of the most important materials of the future. "But something else plays a role at the SDE," says Grafe, "because for the first time these ideas for passive houses were conceived in an existing urban context. The premise was that these examples should be extensions and often additions to existing buildings. No planning of a new building on a green field. These buildings are designed to complement something that already exists, i.e. they are an extension of an existing structure."

Adding storeys is a very important architectural issue right now, because you can't continue to build on the last bit of green space, you actually have to build upwards. "Then it's logical that we also have to investigate lightweight construction. If I build on top, I want to reduce weight. In this case wood as a building material becomes very interesting, because it is less heavy and very adaptable in terms of construction."

The Norwegian Wooden House in the Wuppertal district of Uellendahl-Katernberg on the edge of the Mirker Grove

Photo: UniService Transfer

Timber - the raw material of the future for the construction industry?

The Wuppertal Institute has also been working on sustainable future markets for the renewable raw material wood in the field of new construction and building refurbishment with its project "Holzwende 2020plus". However, is anything really happening in Wuppertal? "In practice, it's still not enough, there's still room for improvement," says Grafe. "The residential areas designated in Wuppertal are very conventional; this is where the materials that the construction industry now offers are used. This case doesn't only apply to Wuppertal; it applies to the whole of Germany. The climate targets in construction are currently often being achieved with materials that are not actually sustainable. An enormous amount of silicone is being used, many materials from the plastics sector are being used, which we not only don't know how they will behave, but also have to assume that they will have to be disposed of in twenty years' time." This is not the case when wood is used as a construction material. In his opinion, there is currently no project in Wuppertal where new steps are being taken in the area of building materials. "These are missed opportunities!" Over the last 25 years, there has been an enormous leap in technological innovation in wood as a building material. Today, it is possible to supply prefabricated wall sections, and in some cases also beams or assembled ceiling constructions, which can do much more, perform much better and guarantee greater spans. "This is in line with climate targets and is also being promoted."

However, the architect concludes by explaining that people's tolerances towards each other must also change. "Timber construction is certainly always wafer-thin compared stone construction, you hear a lot from your neighbours, but with timber we have the freedom to design things ourselves. There are more options than in classic detached house construction."

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Christoph Grafe has held the Chair of Architectural History and Theory at the University of Wuppertal since 2013.