Waterwheel returns to the cheese hammer

A mechanical engineer from the University of Wuppertal is involved in the project

The Käshammer hammer mill in Gelpetal is one of Wuppertal's listed buildings, has a long, eventful history behind it and is now getting its so-called overshot waterwheel back. In addition to generating electricity, it can even produce heat for the building. The University of Wuppertal was also involved in the planning. In an engineering project, mechanical engineering student Niklas Alteköster calculated the design, performance and efficiency of a waterwheel and compared the advantages and disadvantages of a wooden waterwheel with a sheet metal waterwheel.

Waterwheels utilise the energy of water

A waterwheel is a hydroelectric engine that utilises the energy of water. It was invented by Greek engineers in the 4th/3rd century BC and was originally used to irrigate agricultural fields. The first watermill can be traced back to the birth of Christ in the area of the River Inde in Germany. From the 12th century onwards, they were widespread in Central Europe. The waterwheel then experienced a real renaissance during the beginning of industrialisation as a drive for machines, whereby a location with a sufficient water supply was of course the most important criterion.

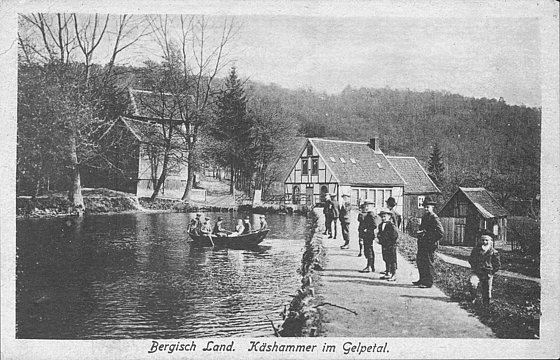

The Käshammer around 1900, view over the Hammerteich, on the left the excursion restaurant,

Photo: public domain

Käshammer hammer mill

Hikers travelling through the Gelpetal will inevitably pass the hammer mill at the Käshammer with its dammed pond. It was added to the monument list of the city of Wuppertal in 1985. The Käshammer was first mentioned in a document in 1607 and was used by farmers as a bone mill (animal bones were crushed in bone mills and used as fertiliser in the form of bone meal in agriculture, editor's note). The name Käshammer has been handed down since 1824. In the 19th century, the hammer mill was operated as a refining hammer (where pig iron was refined into an early form of stainless steel, editor's note). Three overshot water wheels drove the drop hammer and two forge blowers.

At the end of the 19th century, the then owner founded a restaurant at the same location, which is still familiar to many Wuppertal residents, and was a popular destination until 2005.

Today, after many renovations and restorations under preservation orders, the hammer mill is one of the best-preserved historical workshops in Wuppertal.

The overshot waterwheel returns

As part of the debate on renewable energies, experts are also looking at the topic of hydropower, although Germany is hardly investing any money in research projects in this area. Hydropower therefore plays only a minor role in electricity production, although 240 rivers in Germany provide a total flow of five cubic metres per second, from which up to three gigawatts could be generated. At the Käshammer hammer mill, the installation of a top-shaft waterwheel (a top-shaft waterwheel uses cellular wheels. The water flows through a channel or a pipe to the apex of the wheel, where it falls into the cells and sets the wheel in motion through its weight and kinetic energy, note Wikipedia) now achieves an efficient and economical value. The prospective engineer Niklas Alteköster from the University of Wuppertal calculated the requirements for this. He determined the height and volume of water and compared the performance of a wooden wheel with a sheet metal wheel to design the water wheel. As a result, he found that both types of waterwheel would cover the energy consumption of a detached house per year if the water flow were constant throughout the year.

Waterwheel running again

In mid-July, a specialised company from Bavaria installed the waterwheel at the Käshammer hammer mill. Thanks to the interdisciplinary collaboration between the university, the Lower Monument Authority of the City of Wuppertal and a specialist company, the hammer mill is now once again a fine example of a historical building that the current owner has now sustainably equipped for the future after more than 400 years.

Uwe Blass

Niklas Alteköster has been studying mechanical engineering at the Department of Construction at the University of Wuppertal since October 2018. He is currently studying for a Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering, which he expects to successfully complete in spring 2025.