The forgotten winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature

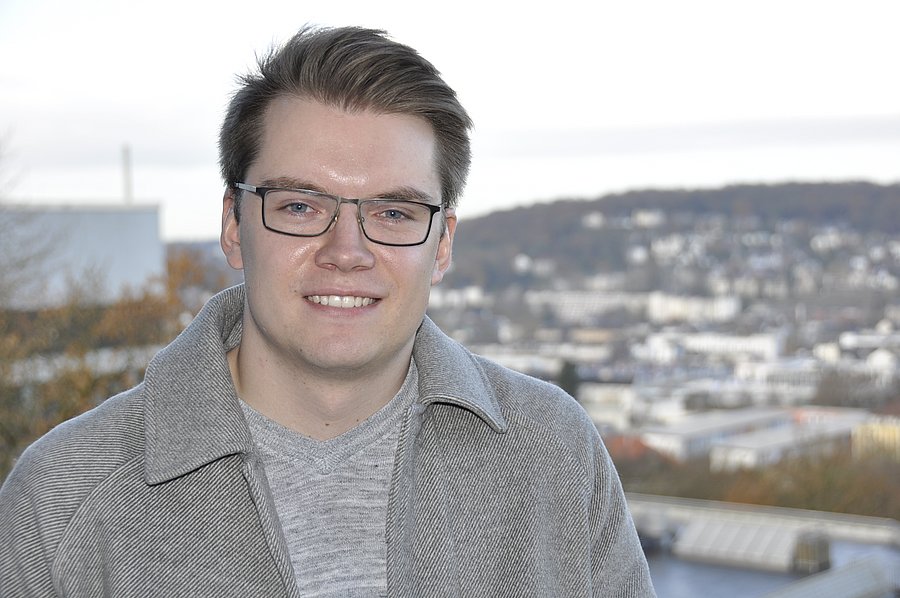

Linus Richter / German Studies

Photo: UniService Transfer

The forgotten winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature

Student Linus Richter organises a conference on the most widely read German writer of the late 19th century: Paul Heyse

Sometimes quite normal seminars at university can be the initial spark to revive long-forgotten topics. In the case of student Linus Richter, it was his encounter with the German writer Paul Heyse, which has now led to a conference at which academics will be examining the exceptional talent of the writing guild at the end of the 19th century.

Drawing landscape with language

Paul Heyse (1830 - 1914) wrote around 180 novellas, eight novels and 68 plays over the course of his life. Despite this, many people today hardly recognise his name. Linus Richter only came across this interesting man of letters by chance, because he was taking part in a seminar in German studies that focussed on German Nobel Prize winners. "The subject really fascinated me. When you read Heyse today, he is still very accessible, both in terms of his language and his themes," says Richter. He is particularly fond of the novellas from Lake Garda, because they express the full range of his ability. "The theme is still popular today as a holiday destination. Heyse manages to draw landscapes with language and that is fantastic. When travelling in Italy, he always had a sketchbook with him and tried to draw the landscape with a pencil. In the novella, he himself admits that he ended up painting with words. It is typical of Heyse to describe landscapes in sophisticated language so that you can visualise them. He has a quality of language that I think hardly anyone would achieve today, and that totally fascinated me, because it's not antiquated."

The most widely read writer of his time

It is hard to imagine that the most widely read writer of his time is hardly known to today's reading public. Perhaps this is because Heyse never wrote a real bestseller in his entire oeuvre, Richter surmises. "Many writers are primarily known for certain works. Even with Goethe, you think of Faust or Werther first, but he also wrote a lot of things that nobody reads today, such as Stella or Hermann and Dorothea. Moreover, the end of many of Paul Heyse's works is not conciliatory, but leaves the reader feeling uneasy. You are then dissatisfied with the outcome." His themes are also no longer topical because he wrote for an audience that no longer exists. Historically, however, he is still interesting because Heyse tells us how people lived and thought during the imperial era. One example is the topic of loyalty.

Familiar with culture from a young age

Born to a professor of philology in Berlin and a mother who came from the Berlin salon culture, Paul Heyse had contact with many writers in his parents' home from an early age. From this he developed his own hospitality, which he cultivated extensively in later years in Munich. "Heyse had studied and completed a doctorate in Romance studies, a subject that was only just emerging at the time. He first studied in Berlin and then went to Bonn. There he studied under the first professor of Romance philology," reports Richter.

As a young man, he was employed by the Bavarian King Maximilian II and came into contact with many academics in the royal dialogue rounds. Richter comments: "You can see that Heyse was very interested in all topics, not just art. These symposia organised by the king were very interesting. First there was a scientific lecture and then one of the writers presented something new that he had written himself. However, these were by no means two blocks, but rather merged into one another. The writers also took part in discussions on scientific topics and vice versa. It was already interdisciplinary, a cross-fertilisation of thought." Heyse was already very topical at the time. Among other things, he had already written a novella on the issue of euthanasia and discussed it within the novella. "It's often the case," continues Richter, "that he poses topical, moral questions and doesn't answer them with a clear yes or no, but gives readers the opportunity to think about them. Heyse did not shy away from sensitive topics."

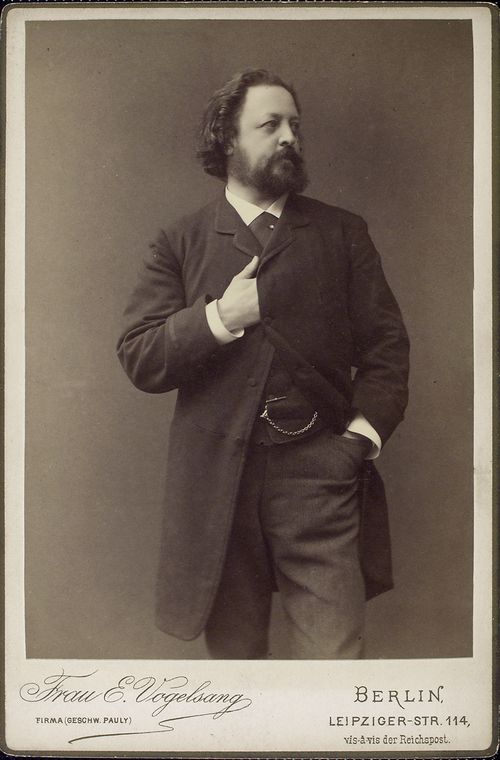

Heyse portrait by Adolph Menzel (1853), public domain

Educational trip to Italy

His relationship with Italy is very interesting. Many of his novellas are set there and he is considered one of the greatest cultural mediators between Italy and Germany in the 19th century. "In 1852, he went on a study trip to Italy in search of unedited writings," reports Richter. "In the meantime, he was also in the Vatican archives in Rome, but was thrown out because he was taking notes. It is clear that it is an educational trip, but unlike most of these journeys, it is not orientated towards Goethe. Heyse travelled to Italy with an open mind and still experienced this incredible feeling, not in Rome, but in Naples, on the Gulf of Sorrento." There he simply lived with the Italians and tried to get to know their mentality. It was not an intellectual exchange, but the experiences of this trip formed the basis of his works, i.e. all his visual impressions of the landscapes and types of people. "His novellas are structured like a theatre play. He has an ensemble with certain character traits. Our idea of the fiery Italian woman actually comes from Heyse. His best-known novella "L'Arrabbiata" translates as "the fiery one". The main character is Laurella, she has curly, long black hair and fiery eyes. That may be a cliché, but it's a common one. Many of the stereotypes we have today originate from Heyse's work, but are now decoupled from it. We have forgotten where they come from."

Munich's favourite host

In Munich, Heyse was not only regarded as a literary role model and influential pope of art, but also as a popular host. The cultural elite literally flocked to his home. "The exciting thing is that he did this on a regular basis. Basically, he had guests every day. You can really compare it to Goethe, who also had his house in Weimar, where everyone went to get recognition from the great poet prince. It was the same with Heyse. Just like Goethe, Heyse had turned his house into a kind of poet's home with lots of objects standing around, so that the stay became an experience." Another aspect of Heyse's life was that he not only invited people to his home, but also corresponded with just as many artists. Accordingly, his estate contains a huge amount of letters. "He wrote dozens of letters every day, stayed in contact with many people and built up and maintained a network of friendships with people who are still very well-known today, such as Theodor Fontane, Theodor Storm, Gottfried Keller and Wilhelm Raabe, all names from the era of realism."

Paul Heyse 1885, public domain

A controversial, uncompromising spirit

Throughout his life, Paul Heyse stood up for his fellow authors. After his poet friend Emanuel Geibel was deprived of his pension in Munich, Heyse also renounced his. When his proposal to admit the poet Ludwig Anzengruber to the Bavarian Maximilian Order was rejected, he resigned from the honourable order. Over time, he became an increasingly self-confident critic of German cultural policy. "He always gets involved in public discussions. He stood up for his fellow writers and always rejected it when poets were penalised for political reasons. He was always in solidarity with his profession," says Richter. He also disliked anti-Semitism, which he also criticised in the German imperial family. "He was very critical of Wilhelm II and saw him as the beginning of the end." The Kaiser denied his Jewish fellow author Ludwig Fulda the prestigious Schiller Prize for his work Talisman. "The comparison between Fulda and Heyse is also interesting because both authors, who were extremely successful at the time, are almost forgotten today. Heyse was the most widely read writer and Fulda the most widely performed. His theatre plays were extremely popular until 1933, which of course has to do with his Jewish origins. It is basically a similar case with Heyse. He had already been forgotten before then, because he had passed his peak around 1900 and when he died, the First World War began. Then there was an insane social change, because society was different after the war. With National Socialism, Paul Heyse's audience simply disappeared." The question that Richter poses for German studies for both authors is how much we have detached ourselves from the literary historiography of National Socialism? "We rely too heavily on tradition. We have certainly lost an incredible number of personalities, because anti-Semitism also plays a role in Heyse's work. He also had Jewish roots. I think Heyse is a warning example that we shouldn't rely on our classics really being the only ones. If I want to understand Theodor Fontane today, I have to look at Paul Heyse."

Third winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature

In 1890, Theodor Fontane believed that Heyse would give his epoch its name and said that the "Heyse Age" would follow Goethe's. In 1910, Paul Heyse became the third German author to be honoured with the Nobel Prize for Literature. The jury's reasoning was: 'as a tribute to the consummate artistry, characterised by ideal conception, which he has displayed during a long and distinguished career as a lyricist, dramatist, novelist and poet of world-famous novellas'.

"What is special about him is his sophisticated language and the structure of his language. His novellas are composed, although that is a dirty word in art, because everything is created in the mind. However, musical works are composed, images are also composed, and this also works in literature. You think about the theme, about the right setting, and in a novel it's all about focussing on exactly that. In a novel or drama, it can sometimes be a little more extravagant. In the novella, however, an unheard-of event - as Goethe put it - should be presented very precisely, and Heyse does this extraordinarily well."

Conference at the University of Wuppertal

It is said that he was the last great narrator of the 19th century when he died shortly before the First World War. The conference is essentially concerned with the literary-scientific examination of Paul Heyse. Richter describes the problem: "Unfortunately, there is still far too little basic research, which is why hardly anyone is interested in him. His literature has not been analysed. At the conference, we are looking at his work in order to be able to categorise him. His correspondence with other writers clearly shows how much he was appreciated, and we will try to find out what distinguishes him from the others and what connects him to them. His legacy is so huge that nobody really dares to tackle it."

The conference organised by Linus Richter in Wuppertal is at least a start.

Uwe Blass

Linus Richter studies German and History at the University of Wuppertal.