The fairytale fountain in Wuppertal

Dr Doris Lehmann / Art history

Photo: Private

A romantic feel-good place in Wuppertal

The art historian Dr. Doris Lehmann about the fairytale fountain in the Zooviertel neighbourhood

There is a very special fountain in the Zooviertel neighbourhood in Wuppertal: The fairytale fountain. It was designed by the Zooviertel architects Rudolf Hermanns and Kuno Riemann, but the fairytale figures were created by Wilhelm Albermann, who designed another fairytale fountain in Cologne-Mühlheim a few years later. Who was this sculptor and what other monuments do we know of him?

Lehmann: Wilhelm Albermann (1835-1913) lived for a long time as a freelance sculptor in Cologne, but was born in Werden an der Ruhr and trained as a wood sculptor in Elberfeld before attending the Berlin Art Academy. His wife Maria, née Kesseler, with whom he had many children, came from Elberfeld and was the daughter of a factory owner. Albermann set up his own productive workshop and a commercial drawing school, became involved in the Association for the Promotion of Sculpture in the Rhineland and Westphalia and took on not only commissions but also other honorary posts. He was eventually awarded the title of professor. Probably his best-known works include the Jan von Werth fountain (1884) on Cologne's Altermarkt and the Barbarossa in Sinzig (1875). Other works by him include the seated statues of the museum donors Wallraf and Richartz (1900) in Cologne. The four monumental caryatids (1879-81), personifications of music, painting, sculpture and architecture, were created for the façade of the old Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf. Today they stand not far from the stovepipe of the installation "Loch" by Josef Beuys and the Kom(m)ödchen. Lost and therefore almost forgotten or less popular today are Albermann's memorials to war dead, Kaiser Wilhelm I, Bismarck and Moltke. The Elberfeld war memorial to those who died in the wars of 1864, 1866 and 1870/71, which was dedicated in 1881 on Königsplatz, today's Laurentiusplatz, was destroyed in the Second World War. Works created for St Laurentius and pediment figures created for Barmen Town Hall in 1877 have also been lost or have not survived.

Which fairytale figures can be found on the Wuppertal fountain?

Lehmann: The Wuppertal fairytale fountain has four relief niches with round arches at the top depicting scenes from Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White and Little Red Riding Hood. Cinderella sits at an open window surrounded by doves that come to her aid. Snow White rests in a death-like sleep surrounded by the seven dwarfs. Sleeping Beauty is approached by the prince and Little Red Riding Hood is accompanied by her admonishing mother and the wolf sneaking up behind her. In addition, four individual figures adorn the fountain, sitting as sculptural pinchers in the area above the scenes: Reineke the Fox, Puss in Boots, Swinegel the hedgehog, who outwits the hare in a race, and King Nutcracker.

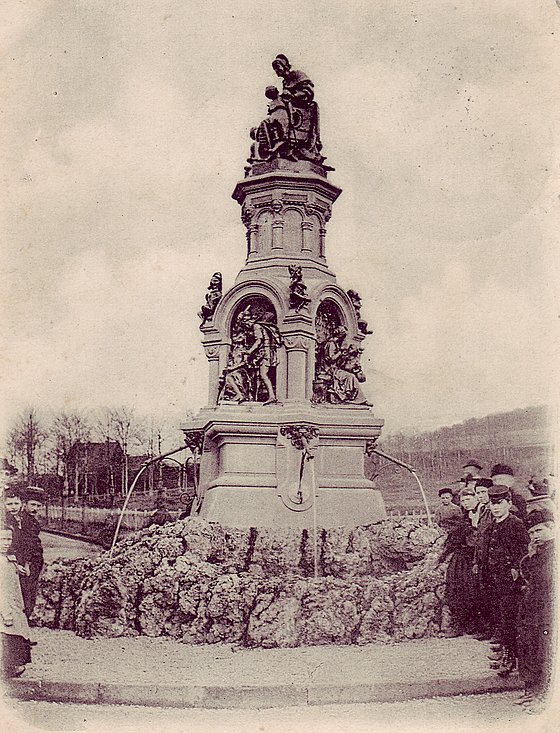

The fairytale fountain 1897

Photo: public domain

At the inauguration ceremony in 1897, government architect Hermanns said in his speech: "The fountain shows the sensitive, noble, chaste conception that characterises all of Albermann's creations, combined with perfect design and attractive grouping." What did he mean by that?

Lehmann: Today we would categorise Albermann's work as romantic historicism. The praise goes to the sculptor's sensitivity for an appealing design that arouses emotions across generations and offers a narrative approach to the popular subjects using pictorial means.

The position of the artwork also played a role. Why was that important?

Lehmann: At the time, the zoo district was in its urban design and development phase, the area directly around the fountain was not yet built on and was more rural in character. The fountain was originally erected on a roundabout, which was created in the centre of Baldurstrasse, Donarstrasse, Jaegerstrasse and Wotanstrasse and united five visual axes due to the course of the street. The planting of avenues of trees was intended to frame these visually.

In addition to yellow sandstone and cast tin, the materials used included slag, from which the basins were moulded. That was an unusual material, wasn't it?

Lehmann: From today's perspective, it certainly was, but in the 19th century, various attempts were made to utilise slag in a meaningful way. Incidentally, further research is currently being carried out into this in the interests of sustainability. When the fountain was built at the end of the 19th century, slag was processed into cinder blocks, and there were even industrially produced cobblestones that were valued for their strength and thermal insulation. Slag was used as a material in road construction, hydraulic engineering, civil engineering and even in house building, and was therefore certainly more widespread than one would expect at first glance. In the case of the Märchenbrunnen, however, the decorative properties of slag were probably the decisive factor in the choice of material, as it was an attractive option for the construction of artificial grottoes at the time. It is fitting that the four collecting basins at the foot of the fountain, where the water collected, were made of slag. The fact that the basins were removed in 1939, turning the fountain into a monument, was explained by the fact that the number of motorists had increased and it could be too dangerous for them to turn round the fountain without slowing down. And this is no fairy tale.

The fountain survived the wars quite well, although some of the figures were lost before 1932. Later, it was in danger of falling into disrepair and for a long time it was questionable whether it could be saved? How did it finally come about?

Lehmann: The fact that the fountain was saved is the result of a concerted effort and great persistence in Wuppertal. Starting with the Sonnborn-Zoo-Varresbeck citizens' association and the Donarstraße primary school, a working group was formed whose successful initiative made the restoration of the fountain possible. Heart and soul and a lot of time were put into the project to finally raise the necessary money: Funding was obtained, but it was not enough. An impressive fundraising campaign was launched at the Fairytale Fountain Festival in 2006. We can be grateful to everyone who took part.

The fairytale fountain today

Photo:

UniService Transfer

The lost fountain figures were reconstructed true to the original based on old photos. How was this achieved?

Lehmann: The photos collected by the residents' association were actually the most important basis for these reconstructions, as historical views of the best possible quality were needed to recreate the figures. The residents rummaged through their collections as well as Ebay and the dissertations on the Zoo neighbourhood and Wilhelm Albermann. Finally, a company specialising in digital sculpture succeeded in the modelling process: digital 3D models were created on the computer to match the fountain, which were refined in consultation between the artists and the residents' association. The figures were then given their sculptural form using 3D printers. After the successful "sitting test" on site, i.e. on the fountain, the models were moulded in an art foundry and transferred as aluminium castings into the form visible today.

The fairytale fountain was deliberately embedded in the staging of the villa colony in the Zooviertel as a romantic place of longing. Has this impression survived to this day?

Lehmann: I think that despite the external changes, the essence of this desire has been preserved and is having an effect in the neighbourhood. The residents' continued identification with their fountain spans generations. In view of the sad news that reaches us from all over the world, places of retreat are booming and the fairytale fountain offers a feel-good place with the longing for a good ending.

Uwe Blass

Dr Doris H. Lehmann is a trained photographer and studied art history, classical archaeology, provincial Roman archaeology and Latin philology at the University of Cologne, where she received her doctorate in 2005. In 2018, she habilitated at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn with a thesis on the dispute strategies of visual artists in modern times and has been a private lecturer ever since. She has been teaching art history at the University of Wuppertal as a research assistant since October 2018.