Historical learning through emotions?

Dario Treiber / History and its didactics

Photo: UniService Transfer

Social media offer the potential to tell history differently

Dario Treiber on historical learning and emotions using the Instagram project "@ichbinsophiescholl"

Historical stories in films are not strange to us. From the 'Cleopatra' with Elisabeth Taylor the Egyptian ruler to the medieval Scottish battle epic 'Braveheart' with Mel Gibson, the Vietnam nightmare 'Apocalypse Now' with Marlon Brando, or the Holocaust drama 'Schindler's List' with Liam Neeson, the medium of film has been dealing with history again and again since its inception. From May 2021 to April 2022, the German television broadcasters Südwestrundfunk (SWR) and Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR) initiated the first Instagram story, which lasted less than a year and dealt with the last ten months of the resistance fighter Sophie Scholl, who was executed during the Second World War. Dario Treiber, a research assistant of the History and Didactics research group at the School of Humanities and Cultural Studies at the University of Wuppertal, is deals with this Instagram project in his doctoral dissertation, including the question: What do the emotions it triggers mean for the reception of history?

@ichbinsophiescholl

New ways of communicating history? Three years ago, the broadcasters SWR and BR posed the hypothetical question of what an Instagram account of resistance fighter Sophie Scholl, who was sentenced to death in 1943, might have looked like and initiated a social media story that lasted almost ten months and was intended to let users participate in the life of the young student. "When the channel went online in 2021, it didn't take long for it to become relatively controversial," says Dario Treiber. "The feature pages were divided between praise and criticism. There was also controversy in history didactics about whether historical topics should be presented in this way." One question that particularly preoccupied Treiber and has now become the subject of his doctoral dissertation was the reception of this Instagram story by schoolchildren, a target group that actually uses this medium on a daily basis. In many comments on the account, users described their emotional reactions to the depictions. "There was a lot of talk about how users felt transported back in time, how they empathised with the historical figures and sometimes even described a physical discomfort when watching the stories," he explains, going on to ask himself: "So if this portrayal can trigger such emotional reactions, what effect does it have on schoolchildren? What influence do these emotionalising depictions have on young people's reception behaviour?"

Imitating real time

Nevertheless, how does the channel evoke emotions? Various modes can be observed on the channel, says the researcher, and this is the intention of the makers. Treiber explains that they also speak of 'close-up and recreated real time' and gives an example: "In the weeks before the arrest, the narrative on Instagram creates a parallel between the last White Rose leaflet and Joseph Göbbels' speech at the Sports Palace, which also took place on 18 February 1943. The channel shows that there was a connection between these two historical events, i.e. that the White Rose wanted to distribute its leaflets before the speech began. Of course, it is a gripping narrative and has a dramaturgical effect. However, there is no historical evidence that there was a connection between the two events. This is a mode of emotionalisation. Historical processes or causalities are altered in such a way that a gripping dramaturgy is created, even though the sources don't actually provide this." As a viewer, however, you are caught up in it, you get excited. Changing historical events can then evoke emotions.

Supposedly living history at Instagram speed

"Social media and historical work are very different in many respects," says Treiber, "social media is short-lived, fast and of course thrives on the fact that you need regular content (qualified content, editor's note). Content had to be created every day for ten months." The problem with this, however, is that the source situation does not allow for this, as it is sometimes not possible to make a statement for several weeks. And so the impact mechanisms of social media are also different. "Nevertheless, they offer the potential to tell history differently. Especially when it comes to the history of National Socialism, we are in a time in which the last contemporary witnesses will soon no longer be alive," Treiber explains, meaning that we need to think about new digital ways to keep the conversation about history going with young people. It is important to be aware of how the new media works.

Project day with three school classes aged 14 to 16

In his doctoral dissertation, Treiber investigates how pupils receive the content of this channel. In particular, he is investigating the influence of emotions on historical thought processes. To this end, he worked with young people from three school classes aged between 14 and 16 and collected data. "At this age, emotions are not usually articulated openly. Therefore, I wanted the pupils to work individually with the channel. They had the task of writing their own commentary on a post they had freely chosen. The aim was to identify indications of emotional reactions." After an initial review of the responses, this also worked. The pupils were very open-minded. "Another method was that the students' recorded group discussions, in which they engaged in dialogue via the channel, took place without my participation." This also increased willingness. "When researching emotions, you always have the problem that although they are felt, they also have to be articulated, and you have to deal with this discrepancy." Treiber now wants to use this data to find out what kind of insights the students gained and to what extent the channel has triggered emotional reactions. "What I can already say is that many pupils consider the Instagram channel a supplement to their history lessons. However, they also know that you have to inform yourself via other media as well. Many people perceive texts and documentaries as more serious than social media."

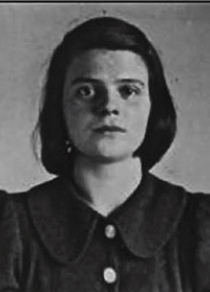

Sophie Scholl (1943)

Photograph by the Gestapo CC0

The medium of film and dealing with history

Contemporary witnesses, non-fiction books and literature can be occasions for historical thinking. However, the medium of film has also influenced the discussion of historical events in the past. "Films have already changed a lot, especially in the discussion about the history of National Socialism," says Treiber and continues, "for example, the broadcast of the series 'Holocaust' in the 1970s or the film 'Schindler's List', which were caesuras that greatly changed the social debate." Social media also represents a turning point because it offers other ways of telling history. There are parallels to film, because the emotionalisation or mixing of fictional and historically verifiable elements alone has long been found in film. "But the form of apparent immediacy is an innovation in social media. While the channel was running, you were shown new content every day; you constantly stumbled across this story and were confronted with it repeatedly. That's a difference to film." One criticism that the scientist shares with many others, however, is the supposed interaction with the historical figures. For example, the makers sometimes answered users' questions in the name of Sophie Scholl.

History in real time - danger of falsifying history?

Films generally reach many viewers, although the makers are not necessarily critical in their approach. A great recent success with the public was the television series 'Sisi', about the Austrian Empress and Hungarian Queen Elisabeth, in which the life story was treated with 'great artistic licence'. Of course, such an approach also harbours the danger of falsifying history. The academic comments: "I definitely recognise this danger. It's a big risk that comes with it. It is important that accounts make these artistic freedoms transparent." On the other hand, it is also clear that the media logics of these platforms serve a different attention economy than scientific work does. In addition, most of the data that scientists work with in this area is held by Meta (Meta is the former Facebook company, editor's note). "The platforms determine how the data can be used. Some of them are very restrictive in terms of how researchers can handle the data." The medium is also incredibly fast moving. There is hardly any opportunity to archive data sustainably. These conditions make research difficult.

The influence of emotions on historical thinking

"There is now a consensus in history didactics that historical thinking is not a purely cognitive process," says Treiber, "an emotional component must always be taken into account. Exactly what role emotions play in this is still relatively unclear, and my study is an attempt to approach this question." In his opinion, the emotionalising representations of the channel @ichbinsophiescholl are particularly suitable for investigating how pupils perceive representations of history on Instagram. "The comments on the channel suggest that these depictions have triggered strong reactions. These emotions that arise when encountering history are what I am trying to explore with the pupils."

Can historical topics emotionalise?

"During the ten-month Sophie Scholl project, there were always moments that touched me emotionally," explains Treiber, and current films about historical events don't leave the researcher cold either. "I recently watched the film 'Zone of Interest' (a film about the commandant Rudolph Höss, who lived with his family next to the Auschwitz concentration camp from 1940 to 1943, editor's note), which left me feeling very depressed." Moreover, the Empire story 'Bridgerton', a fictitious English story, which is at least set in a historical setting, also makes the viewers get excited and this definitely shows the interest in historical topics. The third season of the series was shown in 91 countries, from Canada to Austria and Egypt to Australia, and the social media hype continues.

The Instagram project @ichbinsophiescholl could certainly be applied to other people or events. "Social media," says Treiber in conclusion, "offer the opportunity to tell stories of people and stories of resistance that are not so well known. You can make many perspectives visible."

Uwe Blass

Dario Treiber works as a research assistant in the History and its Didactics team.