Reparation payments of the First World War

PD Dr Georg Eckert/ History

Photo: Mathias Kehren

Reparations for the First World War ended in 2010

Historian Georg Eckert on the adoption of the Dawes Plan 100 years ago

In order to help Germany get back on its feet economically after the First World War, the so-called Dawes Plan was signed in London on 16 August 1924. Why is it called that and what did it contain?

Eckert: The Dawes Plan regulated the reparations payments after the crisis year of 1924 and determined the notoriously controversial amount of reparations. Its core consisted of a bond that made Germany creditworthy and thus solvent again. It was named after the American Charles Gates Dawes, who had made a stellar career in politics and business - most recently as director of the powerful Bureau of the Budget. He was then sent to the Allied Reparations Commission as an expert. Under his leadership, an expert report was initially drawn up by authors who claimed to have approached their task "as businessmen" and not as politicians. Such a mandate for a financial expert is revealing - as is the fact that Dawes was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 1925. The Dawes Plan succeeded in reintegrating Germany as a powerful player in the international financial economy after the fatal crisis year of 1923. In this way, he not only helped Germany, which was now able to reliably pay back the newly defined reparations, to get back on its feet.

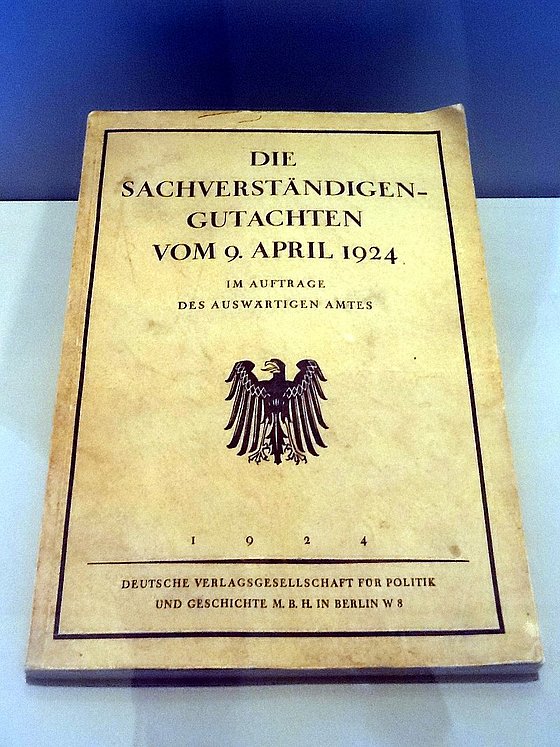

Expert report 1924

Photo: CC BY-SA 4.0

Where did the loans come from?

Eckert : Two types of loan should be mentioned here. Firstly, the Dawes Plan provided for an international loan of 900 million Reichsmarks, which was intended to strengthen the Reichsbank's cover after the fatal hyperinflation. This created confidence and, on the other hand, made other, much larger credit flows possible. American banks and companies in particular were now investing in Germany. This benefited the German economy, American investors and at the same time the Allied reparations recipients. Income from customs duties, taxes and bonds secured the reparation payments. To ensure that these payments could be made, the Reichsbank and the then highly profitable Reichsbahn were reorganised into joint stock companies - something that is almost unimaginable today.

The plan envisaged that Germany would initially repay one billion gold marks in 1924. By 1928, the sum was to increase to up to 2.5 billion gold marks. The problem was that the Dawes Plan did not stipulate an end to the payments. Didn't that mean permanent servitude?

Eckert : Even contemporaries criticised this very vagueness, which could also be called flexibility, because the payments were now based on Germany's economic performance. A few years later, the Young Plan (named after another financial expert, General Electric boss Owen D. Young, who had already helped write the Dawes Plan) was criticised much more harshly. However, in view of the existential hardships in the crisis year of 1923, the players on all sides were comparatively willing to compromise. Although there were vehement dissenting voices in the Reichstag, in the end a two-thirds majority was in favour of the Dawes Plan. After all, it also included the definitive end to the occupation of the Ruhr in 1925. Above all, the acceptance of the Dawes Plan helped to ensure that the economy of the Weimar Republic suddenly boomed. Although the mid-twenties were not quite golden, they were nevertheless a phase of recovery.

Despite the economic upturn, unemployment remained high. Why was that?

Eckert: It depends very much on when you compare the unemployment rates; for example, the labour market at that time was subject to much greater seasonal fluctuations than it is today - agriculture and construction in particular were much more significant. Unemployment in the Reich initially fell rapidly, but then rose again massively from 1927 onwards. However, this was by no means due to the Dawes Plan. Rather, it acted as an economic booster, as it brought American capital to Germany and, above all, signalled confidence. A new era of international co-operation seemed to have begun, giving rise to optimism and a willingness to invest.

It was actually clear from the outset that the sum of 2.5 billion marks could not be raised, wasn't it? And how is the banking crisis from 1929 connected to this?

Eckert : This criticism was also made by contemporaries - although some German "fulfilment politicians" in particular speculated that the Allies would waive unaffordable claims sooner rather than later. In fact, the Dawes Plan was an improvement for Germany in terms of reparations payments. The dispute as to whether the instalments were set realistically has nonetheless continued into more recent research. It has opened up important perspectives, but it is pointless insofar as it is impossible to isolate the instalment amount from other factors. The banking crisis that spilled over from the United States to Europe soon after Black Thursday, which also cannot be reduced to a single cause, certainly did not originate in Germany. One could say that it affected Germany and hit it so hard precisely because the Dawes Plan had been so successful: it was not the reparations payments that now became a huge risk, but the numerous American loans. Investors from the United States suddenly withdrew their capital from Germany in the short term - but this was often tied up in the medium term. There was now simply a lack of foreign currency and money in general. After the hyperinflation crisis of 1923, Germany experienced an almost equally fatal deflation during the Great Depression.

It's hard to believe, but the last payments were only made by the Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Issues in October 2010. What were the reasons for this?

Eckert: Most of the reparation payments were cancelled as a result of the global economic crisis, mainly due to pressure from American and British investors. They brought about a debt cancellation with the argument that maintaining immense reparation claims would do more economic harm than good, even for the recipient states. The bonds from the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan as well as the Kreuger bond were not included in this debt cancellation: these were not actually reparation payments, but investments. Nevertheless, or precisely because of this, the Nazi government no longer serviced them. Only the Federal Republic of Germany as the successor state repaid these debts by 1983, around DM 1.5 billion. This was stipulated in the London Debt Agreement of 1953. The West had learnt from the debate about affordable reparations payments. They were now set so low that the West German budget could in no way be overburdened. At the same time, the interest arrears accrued between 1945 and 1952, around DM 239 million, were deferred until the moment Germany was reunified. As a result, payments were immediately resumed in 1990 and the last instalment was paid on the day before the 20th anniversary of German reunification.

Who did the money actually go to?

Eckert : There were different payment streams, some of which overlapped - that was precisely the logic of the Dawes Plan. The actual reparation payments were to be made to the former opponents of the war, but the core of the Dawes Plan and the other arrangements consisted of three bonds: the Dawes bond, the Young bond and the Kreuger bond. Ivar Kreuger, a Swedish tycoon, invested in the scheme and in return received the monopoly on ignition products. Until 1983, only "Swedish wood" could be sold in Germany. This clearly illustrates the principle that the Dawes Plan had adopted. Reparations were only one aspect of the deal; ultimately, debts between states were expanded into transnational investment transactions.

Do we actually know how much was paid over the years?

Eckert: On the one hand, the sums can be easily traced, but on the other hand, the reparations under the Treaty of Versailles consisted not only of foreign currency payments, but also partly of payments in kind. That makes the calculation more complicated. It was probably around 25 billion Reichsmarks, i.e. only a fraction of the sum of 132 billion gold marks that had been agreed in 1921. Of course, this is a huge absolute amount, but if you focus too much on it, you lose sight of something else: the reparation payments, like the Dawes bond etc., circulated in global financial flows. The decisive player - and also the big winner - was in any case the United States of America. American investors provided the loans, which in turn made the German economy so efficient that Germany was able to pay the reparations imposed on it to the Allies in Europe, who in turn used them to pay off a significant proportion of the enormous debts they had incurred in the United States during the First World War.

Charles G. Dawes

Photo: public domain

The Dawes Plan is still controversial among historians today. Some say that the reparations contributed politically rather than economically to the instability of the first German democracy. How do you see that?

Eckert: There is no doubt that the reparation claims remained an enormous burden for Germany; the Dawes Plan did reduce them and made fulfilment easier to plan. Ultimately, however, it led to a further outflow of foreign currency, or in other words, to an enormous foreign debt, which ultimately exacerbated the effects of the global economic crisis in Germany. Without this fatal economic depression, the voices of those who were now leading political campaigns against reparations would probably have resonated far less. Initially, the Dawes Plan stabilised the economy, both in Germany and internationally; it meant a change of policy for the former Allies, as the British economist John Maynard Keynes had long been calling for. The Dawes Plan strengthened confidence in the economy and in politics, it created reliability for states and private investors alike, and it gave rise to new ties between the former wartime enemies. In this context, co-operation was more promising than conflict. Consequently, the immense financial demands on the Weimar Republic were de facto cancelled in the course of the global economic crisis. But this did not work. Hitler's government in particular constantly pointed out how much Germany had been discriminated against, while no payments had been made since the beginning of the 1930s. The reference to reparations fuelled resentment, and some of this resentment is likely to have played a role in the plundering of occupied countries during the Second World War.

Uwe Blass

Dr Georg Eckert studied history and philosophy in Tübingen, where he completed his doctorate with a study on the early Enlightenment around 1700 with a British focus, and habilitated in Wuppertal. He began working as a research assistant in history in 2009 and now teaches as a private lecturer in modern history.