The Song of the Nibelungs - a heroic epic and its film adaptation

Prof Dr Christian Klein/ German Studies

Photo: UniService Transfer

Lies, betrayal and revenge: The Song of the Nibelungs

German scholar Christian Klein on a German heroic epic and its film adaptation

The Song of the Nibelungs is a medieval heroic epic and was regarded as the national epic of the Germans in the 19th and 20th centuries. Where does the story come from and how old is it?

Klein: The Song of the Nibelungs is a verse epic written in Middle High German between 1150 and 1200 and is one of the most important works of German literature from the High Middle Ages. It is based on an oral Germanic-Scandinavian saga dating back to the 5th century, which takes up historical events and combines them with mythical elements. It must have been a great success with the public at the time it was written - at least the fact that it has survived in thirty-seven (partial) copies speaks in favour of this. Even if there is widespread agreement today that the Song of the Nibelungs is the self-contained work of a single author, we can only speculate about the specific person who wrote it on the basis of clues in the text. Most scholars are certain that the author of the Song of the Nibelungs was an educated, well-read man who came from the neighbourhood of the Passau bishop's court.

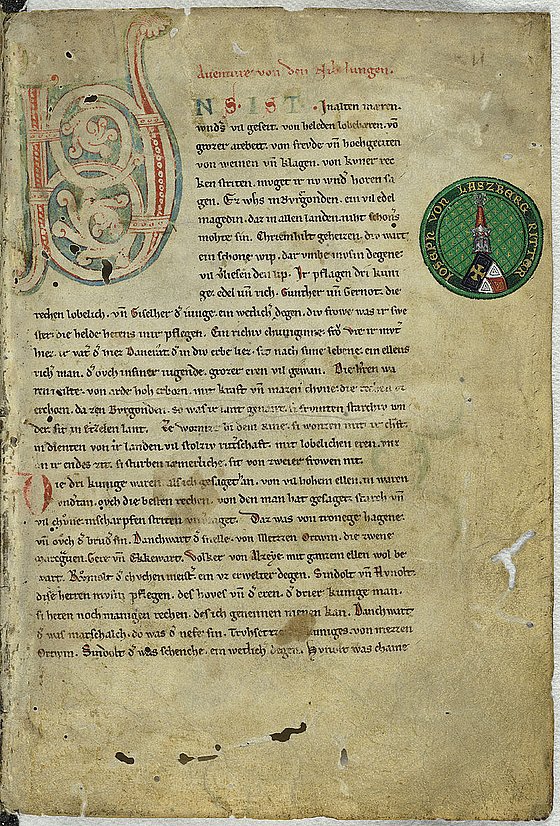

First page of manuscript C

of the Song of the Nibelungs (c. 1220-1250)

Photo: public domain

What is the Nibelungenlied about?

Klein: It's about lies, betrayal and revenge. Very briefly: Siegfried, the son of a king from Xanten, wants to marry Kriemhild, the sister of the Burgundian king Gunther. In return for his consent, Gunther demands that Siegfried helps him to subjugate the fabulously strong Icelandic queen Brünhild so that he can take her as his wife. Invisible under a cloak of invisibility, which he has captured when looting the treasure of the Nibelungs, Siegfried, who is invulnerable after a bath in dragon's blood (with the exception of a small spot on his back), overpowers Brünhild, who believes she has been defeated by Gunther and therefore agrees to marry him. However, deception and violence subsequently develop a disastrous momentum of their own: when the deception is exposed, Siegfried is first murdered by Hagen, who knows Siegfried's 'sore spot' through a trick, with a spear to the back in retaliation for Brünhild's humiliation. Thirteen years later, Siegfried's widow Kriemhild marries Etzel, king of the Huns, whom she manages to persuade after another thirteen years to invite Gunther and his retinue to a feast. Kriemhild's hour of revenge has come after 26 years: She provokes a quarrel, which is followed by a veritable bloodlust. In the end, only Gunther and Hagen are left on the Burgundian side. Kriemhild has her brother beheaded and then cuts off Hagen's head herself. Kriemhild is then beheaded. The remaining knights stand stunned at the scene of the slaughter.

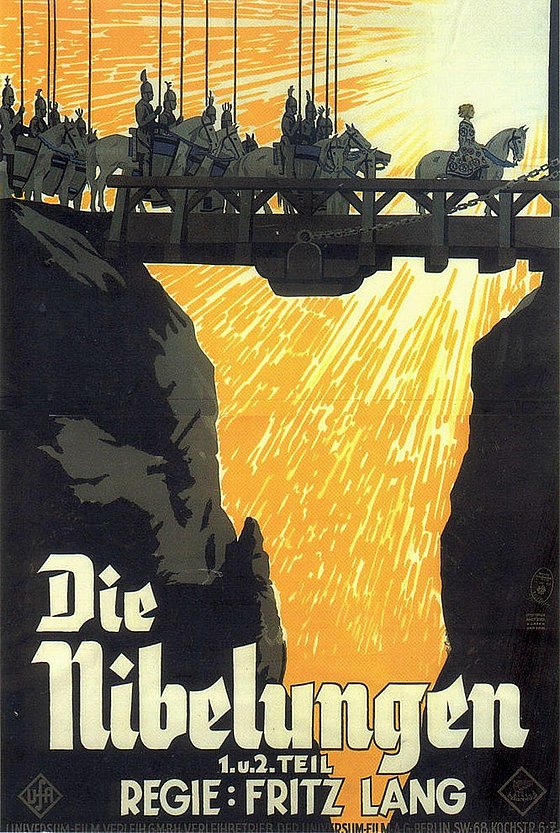

In 1924, the story once again caused a sensation when director Fritz Lang took it on and created another cinematic epic. How did he realise the material?

Klein: In the form of two silent films totalling five hours in length: "Siegfried" and "Kriemhild's Revenge" premiered within a few weeks of each other in the spring of 1924. It was the largest and most expensive film project ever realised in Germany up to that point. In view of the wealth of material, the screenplay had to focus on certain storylines and dramatically intensify them. The whole thing was realised by Fritz Lang in a combination of imagined Germanic mythology, medieval phantasmagoria, Art Nouveau aesthetics and Expressionism, with an abundance of very elaborate buildings - including archaic forest landscapes etc., as it was only shot in the studio. This gives the films a very special atmosphere between realism and dream. Music was particularly important in silent films. Gottfried Huppertz works with the leitmotif technique that Wagner - himself a great fan of the Nibelungen - had established.

Film poster Nibelungen

The Nibelungs 1st and 2nd part, 1924

Photo: public domain

The film was financed during the hyperinflation of 1923, i.e. there was a rock-solid belief in the success of the subject matter, wasn't there?

Klein: It was at least hoped that after the defeat in the First World War, which was widely perceived as a kind of national humiliation, and in times of economic uncertainty, German film audiences would appreciate a film that was conceived as a balm for the 'German soul'. Thea von Harbou, the screenwriter, and Fritz Lang, the director, worked purposefully on the German myth - with blond, noble German heroes against Huns from the East, who are staged as a wild barbarian people. This is also emphasised by the dedication before the first part - "Dem deutschen Volke zu eigen" - which turns what is ultimately supranational material into a national myth. This struck a chord with the times - as the contemporary press put it: "The Nibelung film was born of our time, and Germans and the world have never needed it as much as they do today. We need heroes again!" The film was also a resounding commercial success, the premieres were social events and the films became blockbusters.

It is also remarkable that the screenplay was written by a woman. That was rare back then, wasn't it?

Klein: That's true, but Thea von Harbou, the author of the screenplay and (later) wife of director Fritz Lang, was already a successful writer before she entered the film business after the First World War. From the early 1920s, she was the leading German screenwriter and, together with her husband, formed the 'power couple' of German cinema. The two worked in a kind of artistic symbiosis: Thea von Harbou told the stories that Fritz Lang then brought to life on the screen. In addition to the Nibelung films, the two later set further milestones in film history with Metropolis (1927) and M - Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder (1928).

Today, the staging also allows us to recognise the influence of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, but the visual effects were probably the most exciting. Something like the fire-breathing dragon had never been seen before, had it?

Klein: Fritz Lang did indeed place great emphasis on cinematic spectacle and what we would call 'special effects' today - not only the over twenty metre long dragon that Siegfried defeats, but also trick effects such as Siegfried's disappearance and reappearance under the cloak of invisibility, Brünhild's castle ablaze with flames or the palace fire at the end were spectacular.

The material was really rediscovered during the Enlightenment, in the middle of the 18th century. However, Frederick the Great, to whom the first anthology was dedicated, wrote to the editor, Christoph Heinrich Myller: "Dear honourable friend! You judge much too favourably of the poems from the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries, the printing of which you have promoted and consider so useful for the enrichment of the German language. In my opinion, they are not worth a shot of powder and do not deserve to be pulled out of the dust of oblivion. In my book collection, at least, I would not tolerate such wretched stuff; I would throw it out." How did the king, who was otherwise well versed in literature, come to this judgement?

Klein: The fact that Frederick the Great, as a representative of the Enlightenment, had no interest in the Song of the Nibelungs is more or less in the nature of things. The Song of the Nibelungs seems to negate many of the basic assumptions of the Enlightenment. In any case, man as a rational being who develops civilisation through the application of his intellect is no more at the centre of the Song of the Nibelungs than Kant's Categorical Imperative. A story of slaughter, as presented in the Song of the Nibelungs, must therefore have seemed anachronistic and backward to Frederick the Great.

Against this backdrop, it is remarkable that a special PR campaign was considered for the film release of the Nibelung epic: a wreath was laid at the grave of Frederick the Great with the inscription "For the premiere of the Nibelung film. Fritz Lang" was laid at the grave of Frederick the Great. This ostensible bowing of the director to the Prussian king actually marked his service, as the German identification figure Frederick was used to authenticate the importance of the film for the German national consciousness. Frederick the Great would certainly have expressed his gratitude for this 'homage' in his very own way.

Depiction of Siegfried's murder from manuscript k of the Song of the Nibelungs (1480-1490)

Photo: public domain

One review of the film said that Lang had not created a 'nationalist heroic monument', but 'a dark, consistently stylised fresco of the fateful downfall, in which the driving forces are not love and loyalty, but hatred and revenge'. Why is a total doomsday story still being revisited in literature and film today?

Klein: Let's leave aside whether the criticism is so accurate. But the Nibelung story is certainly still received because it is about the very fundamental realisation that no higher power controls our lives, but that it is our actions - above all emotionally determined ones - that have consequences for us and others. And the Song of the Nibelungs impressively demonstrates just how terrible these consequences can be, showing us what people are capable of. Jan Philipp Reemtsma, our Wuppertal Poetry Lecturer 2024, summarised the conclusion and impact of the Song of the Nibelungs succinctly as follows: "The frenzy has come to an end because there is nothing left to beat. The power of the Song of the Nibelungs lies in the obvious senselessness of it all."

However, the text does not work with one-dimensional figures, but rather creates differentiated characters: Hagen von Tronje is not just the deceitful assassin and Siegfried not just the shining hero who is betrayed. Rather, Hagen is also the politically-minded advisor who acts faithfully and prudently and is prepared to give his own life for the honour of his queen. Siegfried, on the other hand, is also vain and aggressive, quick-tempered and dangerous, because he uses his superiority to egotistically assert his will. His mixture of naivety and overconfidence costs him, who does not think strategically, his life. This, too, is a moral of the story - but one that is often overlooked: Strength alone is of little use if it is not accompanied by cleverness.

The Song of the Nibelungs is written in four-line stanzas that were actually sung and in a language that nobody speaks today. How can such poetry still attract readers today?

Klein: I think that the subject matter of the Song of the Nibelungs is quite universal and therefore also of interest to today's readers. We have all recently been reminded time and again that violence not only characterised past eras, but also shapes our time. The Song of the Nibelungs shows that under certain circumstances, people can be driven to rage ruthlessly and destroy everything. And where a series like "Game of Thrones" is a mega-success, there should actually be an audience for the Nibelungs.

Together with Andreas von Arnauld, you have published the book "Because books change our world". In it, you also refer to the Song of the Nibelungs. What significance does it have for German culture?

Klein: Since the 19th century, the Song of the Nibelungs has been interpreted as a kind of 'manifesto of the German essence' in the context of national self-assurance. At the beginning of the 19th century, when the question of a national identity beyond the small German states became particularly relevant for many, literature took on a special significance as a foundation that created a sense of community. The Song of the Nibelungs was read as a monument to a long-forgotten national poetry in which the "most marvellous masculine virtues", which were interpreted as typically German, manifested themselves. From then on, the Song of the Nibelungs was regarded as a kind of "German Iliad". It had an enormous artistic influence, was adapted many times and interpreted according to the requirements of the time. The dramatic and operatic versions of the Nibelung material by Friedrich Hebbel and Richard Wagner in particular contributed significantly to its popularisation. However, it was never a good omen when politicians decidedly referred to the Nibelungenlied, appealed to 'Nibelung loyalty' or claimed that the German military had only lost the First World War because they had been assassinated from their homeland - like Siegfried von Hagen.

Today, despite all the political ideologising, the Song of the Nibelungs is regarded as an outstanding work of art from the Middle Ages which, with an admirable wealth of detail, provides an insight into the courtly society of its time and makes it clear where lies, betrayal and hatred can lead. As testimony to a masterpiece of human creativity, the three most important manuscripts in which the Song of the Nibelungs has been preserved were recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2009. This meant that the text, which has always been international in terms of its subject matter and tradition, was officially given the status it actually deserves: to be part of the 'memory of mankind' beyond nationalistic appropriation.

Uwe Bass

Prof. Dr Christian Klein teaches and researches in the section Modern German Literary History / General Literary Studies in the School of Humanities.