In search of India

Prof Dr Sandra Heinen/ English Studies

Photo: Berenika Oblonczyk

When a European criticises the exploitative structures of the colonial powers

The English scholar Sandra Heinen on "In Search of India", the last novel by E.M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster is one of the most important English authors of the 20th century. What are the reasons for this?

Heinen: The processes of literary judgement are complex and are influenced by many factors. If you want to find the reason for the author's enduring reputation in the novels themselves, I think the interweaving of culturally specific and universal themes is central. On the one hand, Forster's texts thematise issues that are characteristic of the mentality of classical modernism. It is a time of far-reaching changes that continue to have an effect today and are therefore still of interest. On the other hand, Forster's novels also deal with themes that are relevant across epochs, such as the relationship between inner and outer life or the question of whether and how it is possible to overcome social and cultural barriers. Through this combination of the specific and the general, the texts open up insights into the time of their creation, but have not become purely contemporary documents, but still appeal to readers.

In addition, the fact that Forster formulated a theory of the novel in Aspects of theNovel, which has been recognised in literary discourse, may also have encouraged the reception of his novels. Forster's membership of the famous Bloomsbury Group and the award-winning and commercially successful film adaptations of the novels have certainly contributed to the author's position today.

What was the Bloomsbury Group all about?

Heinen: The Bloomsbury Group was a circle of artists* and intellectuals who were friends (as well as some who were related or married), who came together for regular meetings and had a decisive influence on English modernism. The group is named after the London neighbourhood of Bloomsbury, where many of the meetings took place. An important meeting place was a house in Gordon Square, where the famous writer Virginia Woolf lived with her three siblings from 1904. Other notable people associated with the group include the art critic Clive Bell, the painter Vanessa Bell (Virginia Woolf's sister), the painter Roger Fry, the painter Duncan Grant, the economist John Maynard Keynes, the author Lytton Strachey, the publisher Leonard Woolf (Virginia Woolf's husband) and, from the 1910s, E.M. Forster. The intellectual and artistic exchange strongly influenced the work of the members. Together, the group epitomised the English form of modernism as the cultural high point of the early 20th century.

A Passage to India, his last work, was published on 4 June 1924. What is the novel about?

Heinen: The main theme of A Passage toIndia (In Search of India) is the relationship between the British and Indians in the British colony of British India in the 1920s. The story is largely set in northern India, in a place where the British colonial rulers have established a base from which they rule the country. Two women are travelling from England, for whom the country is new and who are keen to get to know it. Their attempts to encounter the 'real India' end in a court case in which a young Indian doctor is accused of indecently touching the younger of the women. Although the accusations are dispelled, the relationships of trust that had previously developed between the Indian and English characters are fundamentally shaken by the end of the novel.

This novel is also referred to as the 'prototype of post-colonial literature'. What does that mean?

Heinen: The term 'postcolonial' is used today in different senses. Sometimes postcolonial literature is defined by its origin. In this case, it would primarily include texts written in formerly colonised countries. Another use of the term, which often resonates due to the prefix 'post', focuses on the time of origin and views postcolonial literature primarily as literature that looks back retrospectively on a past colonial period. In the sense of these two uses of the term, A Passage to India is not a postcolonial novel, but - to a certain extent the opposite - a colonial novel, because it was written more than 20 years before Indian independence and was also written by a European.

However, there are at least two competing definitions according to which A Passage to India can certainly be described as a postcolonial novel. According to one well-known definition, postcoloniality does not begin with decolonisation, but with the onset of colonisation, which entails profound changes for both societies involved. Finally, another use of the term defines 'postcolonial' neither in terms of time nor space, but as an attitude. Literature would therefore be postcolonial if it criticised colonialism or, more generally, exploitation structures of any kind. This happens unmistakably in A Passage to India with the portrayal of the English colonialists. Forster also makes an Indian character, Dr Aziz, the protagonist of the plot and thus gives a lot of space to the Indian perspective. This already becomes clear in the first scene of the novel, in which several Indians discuss the question of whether one can be friends (as an Indian) with an Englishman. On the other hand, Forster remains true to the colonial discourse in some points by reproducing orientalist stereotypes of the 'other'. The text is therefore both a product of the colonial discourse and a very emphatic criticism of it.

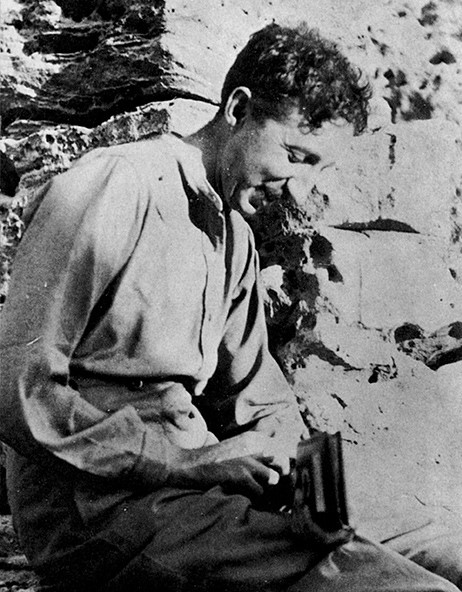

E.M. Forster (1917)

Photo: public domain

Many of Forster's works were made into films in the 1980s and 1990s: A Passage to India (1984), Room with a View (1985), Maurice (1987), Where Angels Fear to Tread (1991) and Howards End (1992). Why so late?

Heinen: Forster didn't have a high opinion of the film and turned down almost all requests. He himself only agreed to the production of two BBC television films: in 1965, a film adaptation of Santha Rama Rau's theatre adaptation of A Passage to India was broadcast (directed by Waris Hussein); this was followed in 1966 by the film adaptation of the short story "The Machine Stops" (directed by Philip Saville). It was not until more than a decade after Forster's death in 1970 that further film rights were granted by the executors of his estate.

The release of the rights took place during a favourable phase for realisation: so-called heritage films, which represented the British past in elaborate historical films and primarily drew on literary models, dominated the British film industry in the 1980s and 1990s. Today, the interest in historical material is seen as a reaction to the social changes brought about by Margaret Thatcher's policies. A separate subgroup of heritage films were productions of stories from the period of British colonial rule in India, to which David Lean's film version of A Passage to India also belongs. Forster's novels - like only the work of Henry James - were perfectly suited to the nostalgic view of the past for which the heritage films became known.

His short story "The Machine Stands Still" was published as early as 1909, in which he anticipates large parts of technological development and warns of its dangers. That makes it highly topical today, doesn't it?

Heinen: "The Machine Stops" is the only science fiction text by Forster, but it is part of a series of fictional future scenarios that were created in the modern era. A fairly well-known earlier English-language text is, for example, The TimeMachine (1895) by H.G. Wells. As in other texts of the genre, Forster uses developments in the real world as the starting point for a thought experiment in which a possible future is outlined. In this case, the increasing mechanisation of the world in the modern age is the phenomenon on whose possible consequences Forster speculates.

In places, the vision of the future he creates does indeed seem like an exaggeration of currently observable developments: People no longer live in social communities, but individually in underground chambers. There is neither the need nor the desire to leave these chambers, because what people need is provided to them by 'the machine' in their own chamber. Direct sensory and social experience is replaced by simulations. Nature on the earth's surface has been destroyed to such an extent that staying outside the machine-controlled chambers is considered deadly. As in our digital age with its virtual worlds, Forster's people voluntarily submit to the machine; the restriction of the world of experience and the dependence on the machine are therefore - unlike in The Time Machine or Fritz Lang's film Metropolis (1927), for example - self-chosen. These parallels are particularly surprising because they seem to anticipate the consequences of digitalisation, even though Forster wrote his text long before the development of the first computer.

With Maurice, he had already written a novel dealing with homosexuality in 1913/14. Why was this novel only published posthumously in 1971?

Heinen: Forster probably never intended to publish the novel during his lifetime, but revised it several times over the course of his life and also prepared a version for posthumous publication in 1960. Despite the changed mood, sexual acts between men were still a criminal offence in 1960. Although the report of a commission set up by the British government following the arrest of a number of prominent men had recommended decriminalisation in 1957, it was not until 1967, ten years after the publication of the commission's report, that the Sexual Offences Act legalised homosexual acts between men in England and Wales. Corresponding legislation for Scotland and Northern Ireland was not passed until the 1980s. When Forster wrote the novel at the beginning of the century, Oscar Wilde's high-profile sentence to prison and forced labour was less than 20 years old and certainly served as a cautionary tale for Forster.

The ending of the novel is interesting in this context. How a fictional story ends is often read as a form of moral judgement by the author: If a character experiences a happy ending, this seems to indicate that the author approves of their character's behaviour and therefore rewards them with a happy outcome. If a story ends unhappily, this can be understood as a criticism of the behaviour of the characters concerned. This convention of 'poetic justice', which was particularly powerful in the 19th century novel, is demonstrated, for example, by the fact that villains rarely get away unpunished at the end of novels of this period, but are usually sanctioned in one way or another. Now Forster was writing in the more liberal early 20th century and - as a resolute alternative to reality - deliberately created a story in which homosexuality is not punished. In the novel's epilogue, Forster describes his concept in retrospect: "A happy ending was imperative. [...] I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows". Because Maurice 's happy ending implicitly normalises homosexuality, it stood in the way of publication during his lifetime, as Forster also emphasises in the same passage.

E. M. Forster

Doctor honoris causa in Leiden (1954),

Photo: CC BY 4.0

One of Forster's most famous quotes is the sentence: "How can I know what I think before I hear what I say?" What does he mean by that?

Heinen: The much-quoted aphorism seems intuitively plausible, but is open to interpretation without further context. In Forster's work, it can be found in Aspects of the Novel, the publication of a lecture series that Forster held in Cambridge in 1927 and in the course of which he entertainingly describes central genre characteristics of the novel. From a narrative theory perspective, Aspects of the Novel is relevant, among other things, because of Forster's distinction between story (sequence of events) and plot (sequence of events with a causal link). With regard to plot, Forster argues that novels should have a coherent and pre-planned plot. Although authors can and should leave their readers in the dark about connections at times, they themselves should have the entire plot in mind when writing. Forster considers approaches to writing without a plan or plot and refers to André Gide's recently published novel The Counterfeiters (1925), which he sees as a 'violent attack' on the plot in his sense. With an anecdote about an elderly lady who reacts to the accusation of being illogical with the well-known sentence (in the original: "How do I know what I think until I see what I say?"), Forster makes fun of Gide's demonstrative refusal of a plan-orientated writing process. The sentence in Aspects of the Novel is therefore expressly not a self-description by Forster, but on the contrary, Forster differentiates his approach from that of the older lady and from that of Gide.

The fact that the sentence is quoted so often is probably due to the fact that it expresses an everyday human experience, namely that thoughts are often only fully developed when speaking, in a catchy and humorous formulation. The fact that this is supposedly a well-known writer's saying lends the sentence additional weight. Its popularity is probably also due to its openness to interpretation: it has been used to explain phenomena as diverse as cognition, creativity and the subconscious. However, a better source for the idea that verbalisation promotes thinking would be Heinrich von Kleist, whose short essay "On the Gradual Production of Thoughts in Speech" (1811) is still well worth reading.

Incidentally, Forster does not present the anecdote of the illogical elderly lady in Aspects of the Novel as his own invention. The fact that Forster is not the author of the well-known sentence, but in fact reproduces a circulating anecdote, can be proven on the basis of an earlier publication by the social psychologist Graham Wallace, who used a slightly different version a year before Forster in his book The Art of Thought (1926).

Uwe Blass

Prof Dr Sandra Heinen works in English/American Studies at the School of Humanities and Cultural Studies in the field of literature and media studies.